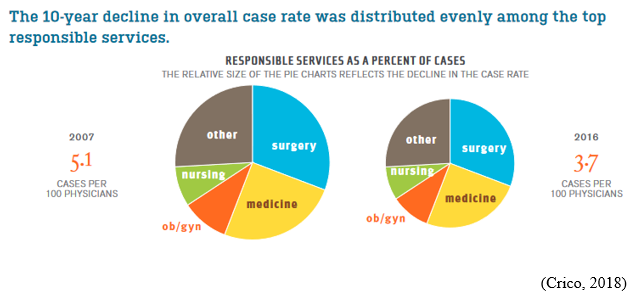

UMBILICAL CORD PROLAPSE: An Obstetrical Emergency

In this blog, I’ll identify what an umbilical cord prolapse is, as well as provide an explanation as to why it is an obstetrical emergency. Additionally, I’ll highlight some of the risk factors that can contribute to a cord prolapse, as well as provide insight as to the standards of care related to management

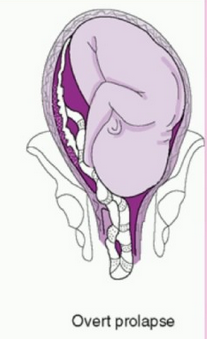

What is an umbilical cord prolapse? An umbilical cord prolapse is identified when the umbilical cord exists the cervical os (opening of the cervix) before the presenting part (e.g. head, buttocks) of the baby.

Types:

- Overt Prolapse: this occurs when the umbilical cord exists the cervix before the presenting part of the baby (e.g. head, buttocks): the cord is palpable (felt) as a pulsating structure in the vagina.

- See title image of overt cord prolapse

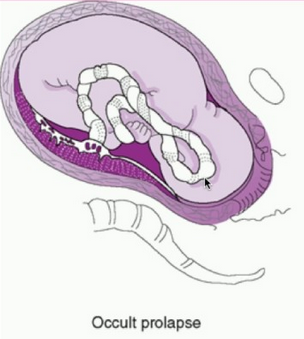

- Occult Prolapse: this occurs when the umbilical cord exists the cervix with the fetal presenting part. The umbilical cord is not visible or palpable (felt) ahead of the presenting part of the baby.

Image of occult cord prolapse: Source – DeCherney et al., CURRENT Diagnosis & Treatment: Obstetrics & Gynecology, 11th ed.

Why is an umbilical cord prolapse an obstetrical emergency? An umbilical cord prolapse is an obstetrical emergency related to the high rate of fetal morbidity and mortality. As a result of an umbilical cord prolapse, the blood vessels within the umbilical cord can become constricted which can cause fetal hypoxia, neonatal encephalopathy, cerebral palsy, and fetal death if not rapidly diagnosed, and managed.

What are the risk factors for an umbilical cord prolapse? There are a number of risk factors that can predispose a woman, and her unborn baby to the sequela of an umbilical cord prolapse. The risk factors include, but are not limited to, malpresentation of the baby (e.g. breech ‘buttocks’ presentation), multiple gestations (e.g. twins), polyhydramnios (excess fluid around baby), preterm rupture of membranes, intrauterine growth restriction, preterm delivery, fetal and umbilical cord abnormalities.

It’s important to note that close to half of umbilical cord prolapse cases are attributable to iatrogenic (caused by medical examination, treatment) causes. This includes amniotomy (artificial rupture of membranes) without an engaged fetal presenting part, attempted external cephalic version in the setting of ruptured membranes, amnioinfusion, placement of a fetal scalp electrode, insertion of an intrauterine pressure catheter (IUPC), or the use of a cervical ripening ballon.

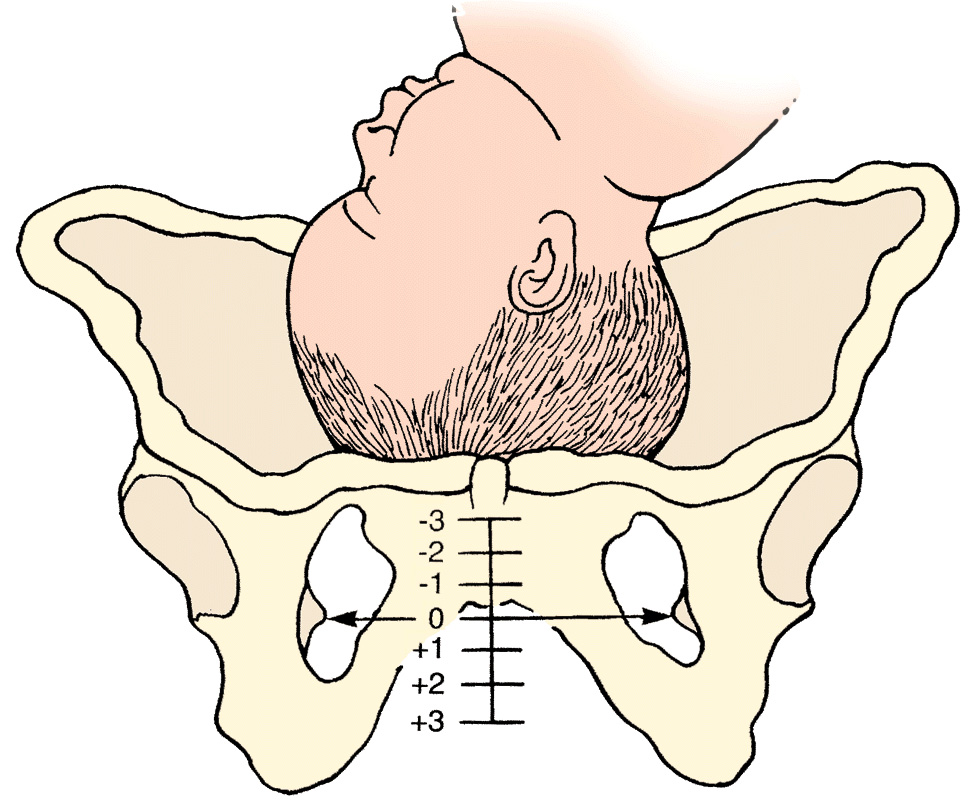

Image of un-engaged fetal head

What’s the standard of care regarding routine amniotomy? According to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), women with normally progressing labor, and no evidence of fetal compromise, the performance of routine amniotomy is not clinically indicated unless required to facilitate monitoring.

Importance of rapid identification: In the presence of fetal bradycardia with ruptured membranes, this should prompt immediate evaluation for potential cord prolapse. Always consider the possibility of an umbilical cord prolapse in the setting of fetal bradycardia, or recurrent variable decelerations, especially if there is an onset of these decelerations that occur immediately after rupture of membranes.

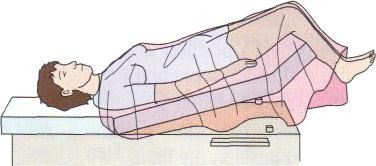

Importance of rapid management: Funic decompression (relieving the pressure on the cord by elevating the presenting part of the baby) should be done manually (with a finger, or hand) by a medical provider or nurse. This is done by placing a finger or hand in the vagina, and gently elevated the presenting part off the umbilical cord. There should be no further pressure placed on the umbilical cord as this may cause spasms of the vessels, and worsen the outcome. The mother should be placed in a Trendelenburg or knee-chest position as these positions can support cord decompression. If the umbilical cord is protruding outside of the introitus (opening of vagina), the umbilical cord should be covered in warm, moist wraps. This is because the room temperate is colder than the temperature inside the uterus which can result in vasospasms within the umbilical cord, and cause fetal hypoxia. As soon as an umbilical cord prolapse is suspected or confirmed, efforts should be made to expedite delivery. This is done typically by means of a cesarean delivery.

Image of Trendelenburg position

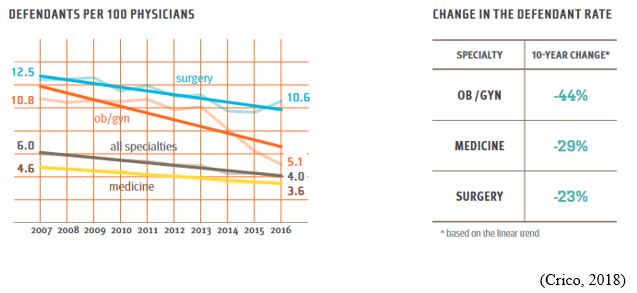

Closing Thoughts: An umbilical cord prolapse is an obstetrical emergency requiring prompt identification, and management in an effort to minimize the risk of injury to the baby. Incorporating multidisciplinary obstetrical emergency drills involving umbilical cord prolapse, and emergency cesarean delivery should be a part of regular simulation training. Practicing role delegation, communication techniques during obstetrical emergencies, and maintaining knowledge of the standards of care related to management of umbilical cord prolapse will reduce the risk of injury to the baby as well as medical legal risk to care providers, and hospital systems.

Resources:

American Academy of Pediatrics & American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. (2017). Guidelines for perinatal care.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. (2021). Approaches to limit intervention during labor and birth.

Association of Women’s Health, Obstetric and Neonatal Nurses. (2021). Perinatal nursing.

Boushra, M., et al. (2023). National Institute of Health, National Library of Medicine.

COMMENT AND SHARE: have you been involved in a root cause analysis involving an umbilical cord prolapse? What was the outcome? What went well with the management? What were some of the opportunities for improvement?