Blog With US

Welcome to Barber Medical Legal Nurse Consulting LLC. We look forward to communicating with you.

Welcome to Barber Medical Legal Nurse Consulting LLC. We look forward to communicating with you.

In this blog I’ll highlight forms of verbal and written communication that are utilized in healthcare settings. Additionally, I’ll provide examples of common communication breakdowns that have been a source of adverse patient outcomes. I’ll close with some suggested risk management strategies.

IMPACT OF COMMUNICATION BREAKDOWNS

Communication breakdowns occur in every area of healthcare, and serve as a common root cause of adverse patient outcomes. The incurred cost of liability related to communication breakdowns is more than one and a half times greater than the overall average total incurred for all nursing professional liability claims. Of 498 closed malpractice claims reviewed, communication failures were identified in half of the claims. Communication errors that involved a failed hand-off report accounted for 47% of the claims. It’s important to note that the majority of the claims could have been prevented with structured, and systematic communication techniques, and hand-off report tools.

TYPES OF COMMUNICATION

For purposes of this blog, I’ll be referring to verbal, and written forms of communication within the healthcare setting. Verbal communication includes, but is not limited to, hand off reports, critical events, status update reports to providers, provider to provider communication, and provider to patient communication. An examples of written communication includes documentation within the legal medical record. It’s important to consider the medical record as a legal document which serves as the most important document for defense of an alleged negligent action, or medical malpractice claim.

RISK MANAGEMENT

There are specific risk management strategies that can promote patient safety, while reducing the risk of medical malpractice allegations for nurses, providers, and hospital systems. For example, creating safe multidisciplinary learning spaces to practice effective communication techniques during critical events. This can be done in the form of implementing and requiring regular multidisciplinary simulation training.

The SBAR technique is a communication strategy that should be practiced, and utilized during hand-off reports, critical events, and status updates to providers. SBAR is a mnemonic that is designed to prompt essential communication elements.

S: Situation – state the patients current condition, reason for admission

Example – Dr. Kim, this is Sharon Jones from labor and delivery. I have Ms. Holland in room 217, a 41-year-old primiparous who has been having a persistent Category II fetal heart rate tracing for 1 hour now.

B: Background – provide relevant medical history, complications

Example – She is of advanced maternal age with an in vitro pregnancy who has a history of chronic hypertension. She was admitted for an induction of labor at 39 weeks 2 days. She received Cytotec for cervical ripening last evening, and has been on Pitocin since this morning.

A: Assessment – summarize the findings from the physical exam, monitoring results

Example – She has a persistent Category II fetal heart rate tracing that has not transitioned back to a Category I tracing with intrauterine resuscitative efforts. I’m concerned because the tracing is now showing minimal variability, absent accelerations, with recurrent late decelerations. The Pitocin has been off now for 1 hour, and interventions remain in progress.

R: Recommendation – suggest next steps for care such as interventions, further monitoring

Example – I need for you to come to the bedside now and evaluate the fetal heart rate tracing and her labor progress.

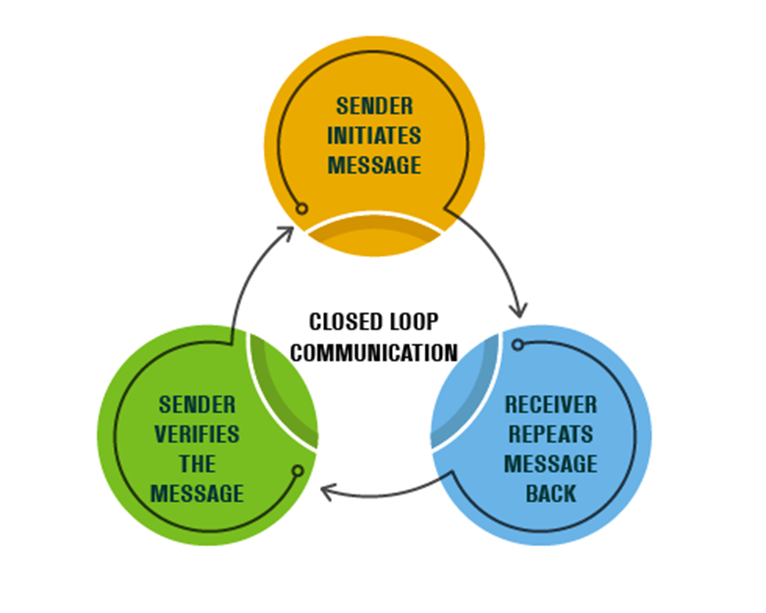

Another method to promote positive patient outcomes, while reducing the risk of litigation, is use of closed-loop communication. In closed-loop communication, the person receiving the instruction or information (receiver) repeats it back to make sure the message is understood correctly. The sender confirms to “close the loop” by verifying the message. This communication tool protects patients from communication errors that can result in adverse outcomes. Closed-loop communication is not just for critical events as it’s encouraged to be used in daily practice to ensure a shared mental model across the many specialties within the healthcare setting.

Example:

Sender: Dr. Smith –

Nurse Jones, please administer 1gram of tranexamic acid IV now to Mrs. Potts.

Receiver: Nurse Jones

Dr. Smith, I’m going to administer 1 gram of tranexamic acid IV now to Mrs. Potts.

Sender: Dr. Smith –

Nurse Jones, correct, you are administering 1 gram of tranexamic acid IV now to Mrs. Potts.

The read back and verify process reduces the risk of communication errors, failures, and delays. It’s recommended that critical findings, test results, and orders be reported verbally (by the sender), then read back by the receiver.

The performance of multidisciplinary board rounds, and bedside report have been shown to promote assessments by all specialties. There’s greater communication among healthcare teams, patients and their families while promoting collaborative decision making. There’s greater continuity of care through coordinated efforts, and greater patient and family engagement in the care delivery process. Both methods reduce the risk of errors by ensuring all perspectives are considered.

Hand-off communication is considered a high-risk activity as distractions and interruptions can serve as barriers to effective nurse and provider hand-off report. This can lead to preventable and costly medical errors, as well as increase the risk of litigation. It’s recommended that a quiet environment be used for hand-off report to promote focus. Hand-off report should be completed separately from other nursing actions, and should include the patient and family to decrease medical errors and enhance communication between the healthcare team and the patient. Active participation by patients and family members promotes patient safety by allowing patients and families to clarify and correct potential inaccuracies. Additionally, it’s recommended that a structured format be utilized to keep discussions concise and on topic. Hand-off tools are recommended as they promote continuity of patient care, while reducing miscommunications.

Efforts should be made to reduce the risk of duplicative documentation as this can be a source of risk to hospital systems, provider, nurses and patients. Duplicative documentation can lead to wasted provider and nurse time, damage to the integrity of the medical records, and medical errors. Standardized documentation checklists can reduce this risk. Additionally, regular chart audits can be done to observe documentation practices, to identify and reduce redundancies and / or omissions.

Communication with providers must be documented in the medical record. Ensure that entries include the name of the provider you spoke with, as well as any changes in the plan of care, and new orders received.

CLOSING THOUGHTS

Documentation is the most time consuming medical and nursing activity which is prone to omissions. There are significant consequences for documentation inaccuracies and omissions such as communication errors, denied insurance reimbursement, lost information for data capture, patient harm, and increased difficulty to defend in litigation.

When documenting in the medical record, remember that the medical record is a legal document. This legal document serves as the most important source of defending allegations of negligence. Healthcare providers and nurses must document objectively, timely, accurately, completely, appropriately, and legibly.

REFERENCES

COMMENT & SHARE: How has documentation influenced a medical legal outcome for you?

In this blog, I’ll identify what an umbilical cord prolapse is, as well as provide an explanation as to why it is an obstetrical emergency. Additionally, I’ll highlight some of the risk factors that can contribute to a cord prolapse, as well as provide insight as to the standards of care related to management

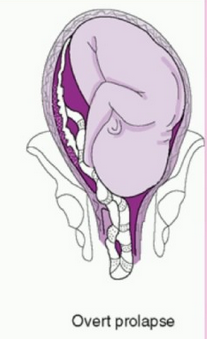

What is an umbilical cord prolapse? An umbilical cord prolapse is identified when the umbilical cord exists the cervical os (opening of the cervix) before the presenting part (e.g. head, buttocks) of the baby.

Types:

Image of occult cord prolapse: Source – DeCherney et al., CURRENT Diagnosis & Treatment: Obstetrics & Gynecology, 11th ed.

Why is an umbilical cord prolapse an obstetrical emergency? An umbilical cord prolapse is an obstetrical emergency related to the high rate of fetal morbidity and mortality. As a result of an umbilical cord prolapse, the blood vessels within the umbilical cord can become constricted which can cause fetal hypoxia, neonatal encephalopathy, cerebral palsy, and fetal death if not rapidly diagnosed, and managed.

What are the risk factors for an umbilical cord prolapse? There are a number of risk factors that can predispose a woman, and her unborn baby to the sequela of an umbilical cord prolapse. The risk factors include, but are not limited to, malpresentation of the baby (e.g. breech ‘buttocks’ presentation), multiple gestations (e.g. twins), polyhydramnios (excess fluid around baby), preterm rupture of membranes, intrauterine growth restriction, preterm delivery, fetal and umbilical cord abnormalities.

It’s important to note that close to half of umbilical cord prolapse cases are attributable to iatrogenic (caused by medical examination, treatment) causes. This includes amniotomy (artificial rupture of membranes) without an engaged fetal presenting part, attempted external cephalic version in the setting of ruptured membranes, amnioinfusion, placement of a fetal scalp electrode, insertion of an intrauterine pressure catheter (IUPC), or the use of a cervical ripening ballon.

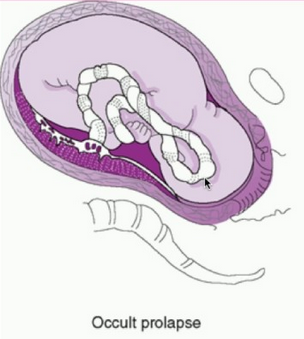

Image of un-engaged fetal head

What’s the standard of care regarding routine amniotomy? According to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), women with normally progressing labor, and no evidence of fetal compromise, the performance of routine amniotomy is not clinically indicated unless required to facilitate monitoring.

Importance of rapid identification: In the presence of fetal bradycardia with ruptured membranes, this should prompt immediate evaluation for potential cord prolapse. Always consider the possibility of an umbilical cord prolapse in the setting of fetal bradycardia, or recurrent variable decelerations, especially if there is an onset of these decelerations that occur immediately after rupture of membranes.

Importance of rapid management: Funic decompression (relieving the pressure on the cord by elevating the presenting part of the baby) should be done manually (with a finger, or hand) by a medical provider or nurse. This is done by placing a finger or hand in the vagina, and gently elevated the presenting part off the umbilical cord. There should be no further pressure placed on the umbilical cord as this may cause spasms of the vessels, and worsen the outcome. The mother should be placed in a Trendelenburg or knee-chest position as these positions can support cord decompression. If the umbilical cord is protruding outside of the introitus (opening of vagina), the umbilical cord should be covered in warm, moist wraps. This is because the room temperate is colder than the temperature inside the uterus which can result in vasospasms within the umbilical cord, and cause fetal hypoxia. As soon as an umbilical cord prolapse is suspected or confirmed, efforts should be made to expedite delivery. This is done typically by means of a cesarean delivery.

Image of Trendelenburg position

Closing Thoughts: An umbilical cord prolapse is an obstetrical emergency requiring prompt identification, and management in an effort to minimize the risk of injury to the baby. Incorporating multidisciplinary obstetrical emergency drills involving umbilical cord prolapse, and emergency cesarean delivery should be a part of regular simulation training. Practicing role delegation, communication techniques during obstetrical emergencies, and maintaining knowledge of the standards of care related to management of umbilical cord prolapse will reduce the risk of injury to the baby as well as medical legal risk to care providers, and hospital systems.

Resources:

American Academy of Pediatrics & American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. (2017). Guidelines for perinatal care.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. (2021). Approaches to limit intervention during labor and birth.

Association of Women’s Health, Obstetric and Neonatal Nurses. (2021). Perinatal nursing.

Boushra, M., et al. (2023). National Institute of Health, National Library of Medicine.

COMMENT AND SHARE: have you been involved in a root cause analysis involving an umbilical cord prolapse? What was the outcome? What went well with the management? What were some of the opportunities for improvement?

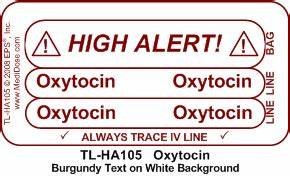

It’s estimated that approximately half of all paid obstetrical litigation claims involve allegations of Pitocin misuse. Recognizing that Pitocin is a high alert medication warranting safe initiation, and management consistent with standardized evidence-based practices reduces patient harm, while reducing litigation risk for perinatal team members, and hospital systems.

In this blog, I’ll identify what Pitocin is, and what it’s used for. I’ll also address why Pitocin is considered a high alert medication. Additionally, I’ll highlight common allegations related to Pitocin management identified in past obstetrical related law suits. I’ll close by offering some risk management approaches that can be integrated into practice.

What is Pitocin? Pitocin is the synthetic (made by chemical synthesis) form of oxytocin, and serves as the most common labor induction agent. Pitocin is chemically, and physiologically identical to endogenous oxytocin that is made, and circulated by the body. Endogenous oxytocin is synthesized by the hypothalamus in the brain, then is transported to the posterior lobe of the pituitary gland where it is then released into maternal circulation. Oxytocin is typically released in response to breast stimulation, sensory stimulation of the lower genital tract, and cervical stretching which results in uterine contractions. The half-life of Pitocin is between 10-12 minutes with uterine response typically occurring within 3-5 minutes of intravenous (IV) administration.

What are high alert medications? High alert medications are defined as those bearing a heightened risk of harm when they are used in error, and that may require special safeguards to reduce the risk of error.

In 2007, Pitocin was added to the Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP) list of high-alert medications due to the potential negative maternal, and fetal effects (patient harm) that can occur when used in error, such as inappropriate timing of administration, and/or excessive dosing.

It’s important to note that Pitocin administration using pharmacological principles can be therapeutic during labor. Pitocin is not a high-risk or dangerous drug, but rather a high-alert medication warranting safe initiation, and management. If managed properly, Pitocin has no inherent risks.

Examples of other high alert medications utilized in labor and delivery settings, include:

General Incidence of Adverse Drug Events (ADEs): It has been reported that 400,000 Americans die annually as a result of medication errors. In 2016, the CDC identified unintentional death, including medical mistakes, as the third leading cause of death in the U.S. The CDC’s Healthy People 2030 indicated that annual adverse drug events (ADEs) or harm resulting from medication errors, have led to 1.3 million emergency department encounters, 350,000 hospitalizations, and over $3.5 billion in excess medical costs. ADEs remain a significant public health issue, with most instances being preventable.

How do ADEs relate to the use of Pitocin? Pitocin is the most frequently used medication for labor induction, and augmentation. Additionally, Pitocin is the medication most commonly associated with preventable adverse events during childbirth. The risks of Pitocin are generally dose related, and include uterine tachysystole, excessive uterine activity, fetal compromise, neonatal acidemia, placental abruption, and uterine rupture.

Other types of Pitocin errors, and ALERTS include:

Risk Management Perspectives: It’s estimated that approximately half of all paid obstetrical litigation claims involve allegations of Pitocin misuse.

Pitocin management also serves as a source of clinical conflict between nurses, midwives, and physicians during labor. Such clinical conflict increases the risk of patient harm, and litigation. By developing a shared mental model across specialties, and incorporating agreed upon standardized policies, clinical conflict, and inter-observer variability is reduced leading to positive birth outcomes, as well as less liability risk for the perinatal teams, and hospital systems.

Additional Risk Management Strategies:

The purpose of this blog is to educate, and inform in an effort to promote patient, and perinatal team safety, promote positive birth outcomes while reducing the incidence of obstetrical related medical malpractice lawsuits by lowering the recurrence risk of errors.

References

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2020. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 107: Induction of labor.

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, 2020. Condition of participation: 42 C.F.R.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2024. Leading causes of death.

Institute for Safe Medication Practices, 2024

Makary, 2016. Medical error – The third leading cause of the death in the U.S.

Simpson, et al., 2021. AWHONN Perinatal nursing, 5th ed.

The Joint Commission, 2021. Standards NPSG. Comprehensive accreditation manual for hospitals.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2030.

COMMENT AND SHARE: Do you have experience with an adverse drug event related to Pitocin? What was the outcome? Were organizational, or system changes made to minimize the risk of recurrence?

In this blog, I’ll review basic uteroplacental physiology in labor, as well as the components of a complete uterine activity assessment. I’ll highlight some litigation trends related to uterine activity in labor, and close with risk management approaches.

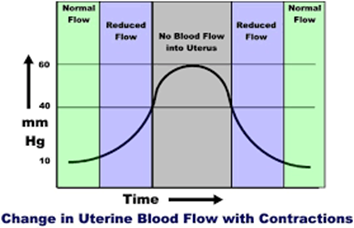

Physiology Basics: The uterus is a muscle that contracts in labor. Blood supply to the uterus, placenta, and fetus is dependent on maternal blood pressure, as well as uterine activity (e.g. contractions). With every labor contraction, the blood supply to the uterus, placenta, and fetus is reduced by 60%.

Fetal (In)Tolerance to Labor Contractions: Excessive uterine activity can have an adverse effect on fetal oxygenation, and the acid-base status of the fetus. Excessive uterine activity can result in decreased fetal cerebral oxygen saturation, as well as fetal acidemia (fetal blood with high levels of acid, or a low pH). Excessive uterine activity can result in birth injuries, specifically, hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy, subsequent cerebral palsy, and possible death.

Excessive uterine activity can have an adverse effect on uterine re-perfusion as well. In the presence of anaerobic metabolism, elevated uterine lactate levels can develop. This can result in inadequate labor contractions, ultimately leading to Pitocin augmentation, cesarean delivery, postpartum hemorrhage, and associated sequelae.

The number one cause of fetal intolerance to labor contractions is inadequate re-perfusion due to inadequate relaxation time between contractions.

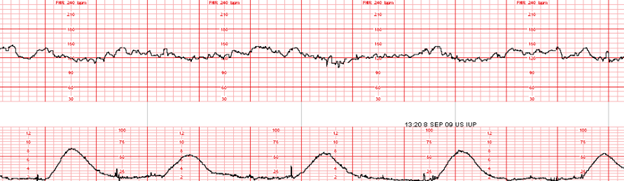

Complete Assessment of Uterine Activity: The assessment of the fetus should not be performed in the absence of a complete assessment of uterine activity. Components of uterine activity assessment, and documentation include –

What is Excessive Uterine Activity? All definitions for excessive uterine activity apply to both spontaneous, and induced, or augmented labor. The evaluation of the presence, or absence of uterine tachysystole, in addition to evaluation of contraction duration, uterine resting tone, and relaxation time between contractions.

Management of Excessive Uterine Activity: Management of excessive uterine activity should not be based on the presence or absence of FHR changes.

The goal of management is to identify, and promote normal uterine activity, and correct the underlying cause of any type of excessive uterine activity.

EXCESSIVE UTERINE ACTIVITY SHOULD TRIGGER INTERVENTIONS, REGARDLESS OF THE FHR STATUS

Uterine Tachysystole, and Excessive Uterine Activity: A Common Area of Liability

Case Study (10/07/2020)

A 28-year-old gravida 2, para 1 at 37 weeks gestation presented for a scheduled Pitocin induction of labor for preeclampsia without severe features.

Admission assessments were unremarkable, with a baseline favorable cervical examination of 3/80/-1. The labor course was complicated by a recurrent Category II FHR tracing in the presence of excessive uterine activity. The patient progressed to complete dilation, attempted to push with contractions, resulting in an onset of fetal bradycardia. An emergency cesarean delivery occurred resulting in delivery of a viable male weighing 7#2oz with Apgar scores of 1/3/3/3/5. A venous cord gas revealed metabolic acidemia: pH 6.94, BD 14.6. An arterial cord gas was unable to be obtained.

The newborn was diagnosed with hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy (HIE), and received therapeutic hypothermia. The newborn had an onset of seizures at seven hours of life. A brain MRI was performed on day of life five revealing a watershed pattern of injury. The newborn was discharged home with the parents on day of life 16. The infant suffers from spastic cerebral palsy with profound neurodevelopmental delays.

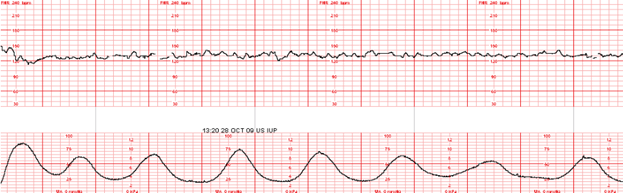

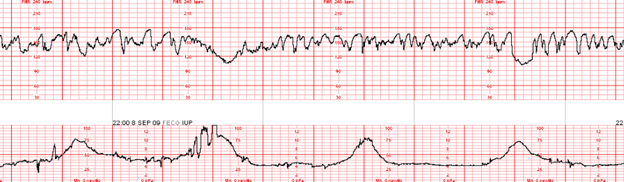

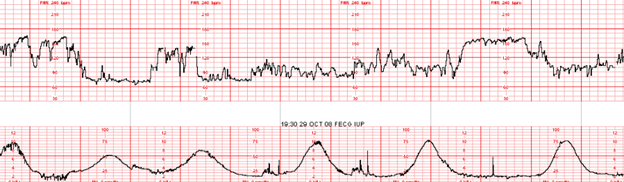

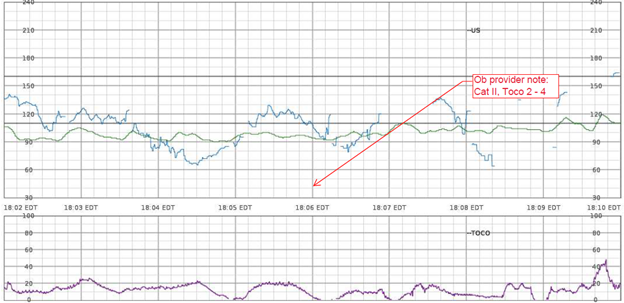

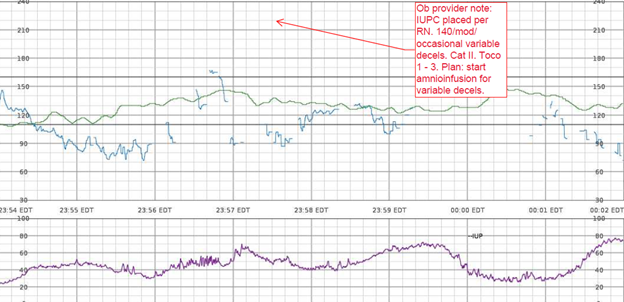

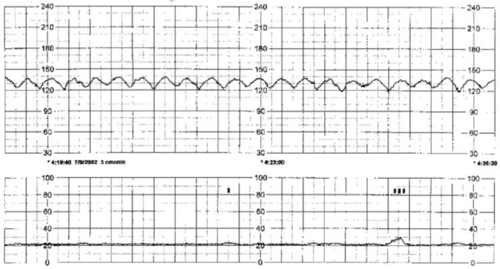

EFM Tracing with Annotated Segment of Ob Provider Note:

Nurses Notes: RN notes indicate a “normal” uterine contraction pattern, normal duration of contractions, and a “soft” resting tone throughout labor.

Q: What assessments are missing specific to uterine activity?

A: contraction duration, resting tone in mmHg, relaxation time between contractions, MVUs in the presence of an IUPC, uterine, and fetal responses to interventions

Litigation Case Theme: Failure of the perinatal team to treat a Category II FHR tracing in the presence of uterine tachysystole, and excessive uterine activity resulting in HIE, and subsequent permanent neurological injuries.

Plaintiff Allegations:

Failure to appropriately identify and treat uterine tachysystole, and excessive uterine activity in the presence of a Category II FHR tracing in a timely manner

Failure to discontinue oxytocin in the presence of excessive uterine activity, and a Category II FHR tracing

Inappropriate oxytocin management

Failure to initiate intrauterine resuscitation

Failure to follow oxytocin orders, and policy

Failure to activate the chain of command when there was clinical disagreement between the nurse, and responsible physician

Defenses:

The fetal injury likely occurred during the antenatal period; therefore, actions during labor and delivery had no impact on the outcome

The standard of care was adhered to

Documentation reflected prompt, and appropriate actions by the perinatal team

Electronic fetal monitoring cannot be used as a diagnostic tool; therefore, birth injury cannot be attributed solely to FHR interpretation

Standard of Care Takeaways (Risk Management Approaches): the evaluation of uterine activity must occur, and is equally as relevant as the assessment of the fetal heart rate.

Conclusion: The assessment of uterine activity during labor is crucial, and is considered a patient safety issue. Applying known parameters to the assessment of uterine activity influences management decisions, forms the basis of safe use of labor stimulants, and provides a means of defining excessive uterine activity among the multidisciplinary perinatal team.

The goal of this blog post is to improve birth outcomes, reduce liability risk to perinatal care providers, educate perinatal team members to avoid the risk of recurrence of errors, while supporting the reduction of obstetrical related medical malpractice lawsuits.

References:

AAP, ACOG (2017). Guidelines for Perinatal Care

ACOG (2009). Induction of Labor

ACOG (2010). Intrapartum Fetal Heart Rate Tracings

AWHONN (2014). Perinatal Nursing

AWHONN (2021). Perinatal Nursing

AWHONN (2022). Intermediate Fetal Monitoring Course

Miller et al., (2022). Mosby’s Pocket Guide to Fetal Monitoring

Rimsza et al., (2024). Association between Elevated Intrauterine Resting Tone during Labor and Neonatal Morbidity. American Journal of Perinatology

Ross et al., (2002). Use of umbilical artery base excess: algorithm for the timing of hypoxic injury. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology

Turner et al., (2020). The physiology of intrapartum fetal compromise at term. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology

COMMENT AND SHARE: What is your experience with a lawsuit involving uterine tachysystole, or excessive uterine activity? What was the case theme? Did the case go to trial? What was the case verdict?

You can learn so much from the metadata in the electronic health record (EHR). Metadata is data, about data.

Example: data entered, patterns of missing data, when data was entered, who entered it, who viewed it, how long it was viewed for, and whether it was modified.

Metadata can identify incidences of errors, as well as patterns of patient care delivery (i.e., recurrent late entries)

Metadata is discoverable per the Federal Rules of Civil Procedures. This means that attorneys can acquire access to EHR information, including the metadata, through the discovery process. Metadata is typically obtained by a computer-generated record of audit trails showing user access and actions.

Providers Can Minimize Risk by Effectively Documenting: During the litigation process, metadata can play an integral role in determining the credibility of evidence, including healthcare provider’s testimony, and documentation.

Metadata analysis can support — or not support — a lawsuit. Frequent errors, and errors of omission can negatively impact a healthcare providers credibility in court. Contrary, metadata that demonstrates complete, and accurate documentation can help exonerate healthcare providers by bolstering their credibility, and providing evidence that adherence to organizational policies, and procedures, as well as standards of practice were followed.

RESOURCES

P.S. COMMENT & SHARE: What has been your experience utilizing metadata to support your medical legal cases?

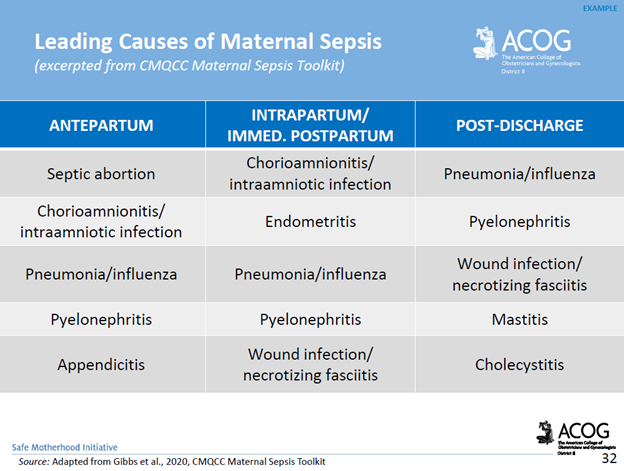

In this blog, I’ll be introducing a maternal sepsis case study, followed by supportive content to enhance the readers understanding of the incidence of maternal sepsis in the U.S., causes, risk factors, and complications that can occur as a result of maternal sepsis. I’ll provide information on the recommended screening, diagnostic criteria, as well as assessment, and treatment recommendations.

Case Study: A 38-year-old woman, gravida 6 para 5, with an unremarkable past medical history presented to labor and delivery in active labor at 39 weeks of gestation and delivered vaginally shortly thereafter. Delivery was uneventful, without regional anesthesia and without perineal tears nor other complications. Twenty-four hours after delivery, the patient developed isolated left lower quadrant pain. Physical examination, abdominal ultrasound, and laboratory tests including complete blood count and basic metabolic panel were unremarkable, and the pain subsided after a bowel movement. On the following day, abdominal pain worsened, while the patient remained afebrile and was hemodynamically stable. Clinical assessment and physical examination of the pelvis and abdomen by the gynecological and surgical teams were unremarkable and revealed no acute distress; the abdomen was soft and non-tender on palpation, and bowel sounds were normal in all four quadrants. Notably, there was a significant discrepancy between the symptoms (referred abdominal pain) and the objective clinical findings. An abdominal and pelvic CT scan demonstrated normal post-partum uterus, endometrium and pelvic organs without signs of acute pathology. A large fecal burden throughout the colon was seen, suggesting possible constipation. Subsequently, 60 h after birth, her clinical condition deteriorated as the patient developed tachycardia with 130 beats per minute, tachypnea with 20 breaths per minute, and blood pressure of 103/65 mmHg. Laboratory values included a white blood cell count of 1.5 × 109/L and C-Reactive Protein (CRP) of 27.1 mg/dl and Lactic acid of 4.05 mmol/L. Creatinine, liver-function tests, and electrolytes were within the normal range. Due to a high clinical suspicion of puerperal sepsis at this point, a wide-spectrum antibiotic regime of ampicillin, clindamycin and gentamicin was initiated, and the patient was transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU). Shortly afterward, the patient became hemodynamically and respiratorily unstable and required sedation, mechanical ventilation, and the use of inotropes to maintain adequate blood pressure. Laboratory results revealed worsening leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, and lactic acidosis. A post-contrast computed tomography scan showed an enlarged uterus with abundant periovarian and peritoneal fluid. Since the presence of pus in the abdomen was suspected and due to the severe clinical deterioration, an emergency exploratory laparotomy was executed, during which 600 ml of thick yellowish-white abdominal fluid was aspirated. The uterus and both ovaries were swollen, necrotic, and covered with fibrin, therefore a total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy were performed. Ovarian preservation was not possible because of severe necrosis. Gross findings of the post-operative pathological specimen showed an ischemic and partially necrotic uterus, while microscopic examination of the uterus revealed a severe acute inflammatory process with necrotic myometrium and bacterial colonies, confirmed later to be Streptococcus pyogenes on blood-agar medium culture. Post-operatively, the patient underwent a prolonged recovery period and was discharged without any further obstetrical or gynecological complications (Kabiri D, et al., 2022. Case report: An unusual presentation of puerperal sepsis. Front Med).

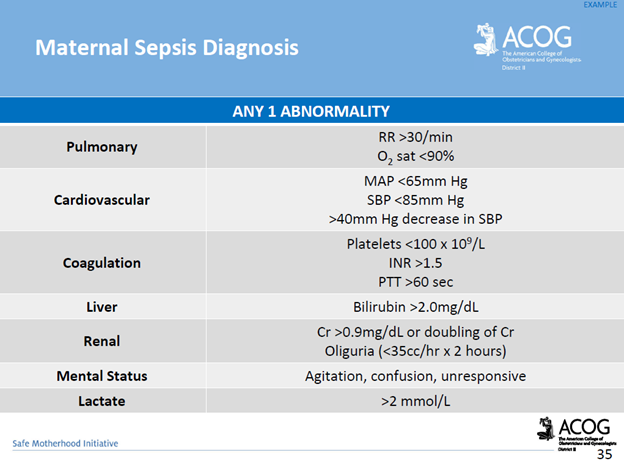

What is Maternal Sepsis: Maternal sepsis is a life-threatening condition defined as organ dysfunction resulting from infection during pregnancy, childbirth, post-abortion, or postpartum period.

The most common pathogens that cause maternal sepsis include Streptococcus pyogenes, Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, Group B Streptococcus, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), Clostridium septicum, and Morganella morganii.

Clinical Presentation: The normal changes of pregnancy complicate identification, and treatment of maternal sepsis. Pregnant patients appear clinically well prior to rapid deterioration with the development of septic shock, multiple organ dysfunction syndrome, or death. This is due to pregnancy-specific physiologic, mechanical, and immunological adaptations (JAMA, 2021).

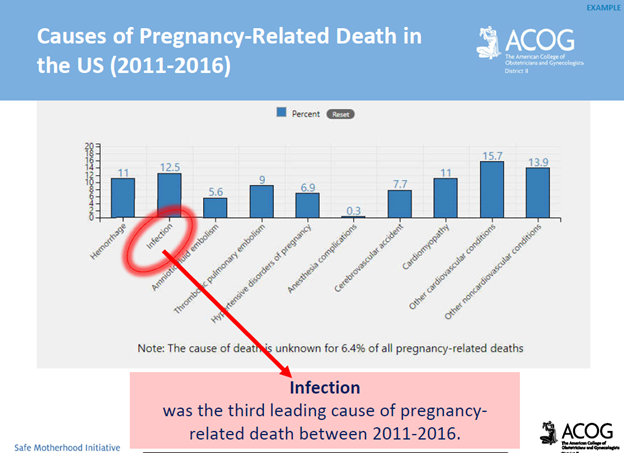

National Statistics: Maternal sepsis is the second leading cause of pregnancy-related death in the United States. Among all pregnancy-related deaths in the U.S., 12.5% are attributed to sepsis (JAMA, 2021). It is estimated that 4 to 10 per 10,000 live births are complicated by maternal sepsis (ACNM, 2018). Rates of pregnancy-associated sepsis are increasing in the U.S., as are rates of sepsis-related maternal deaths.

*Approximately 40% of maternal sepsis cases are preventable with early recognition, early escalation of care, and appropriate antibiotic treatment (Kabiri D. et al. 2022).

Risk Factors: Risk factors for maternal sepsis include advanced maternal age, preterm premature rupture of the membranes (PPROM) and preterm delivery, multiple gestation pregnancies, cesarean delivery, retained products of conception, post-partum hemorrhage, and maternal comorbidities. It’s important to note that maternal sepsis occurs in patients without risk factors.

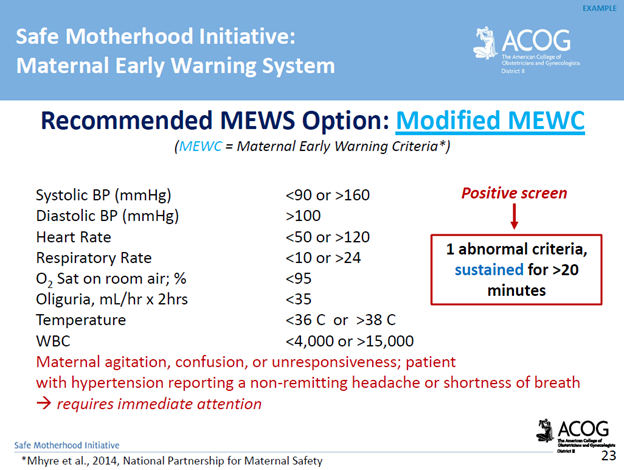

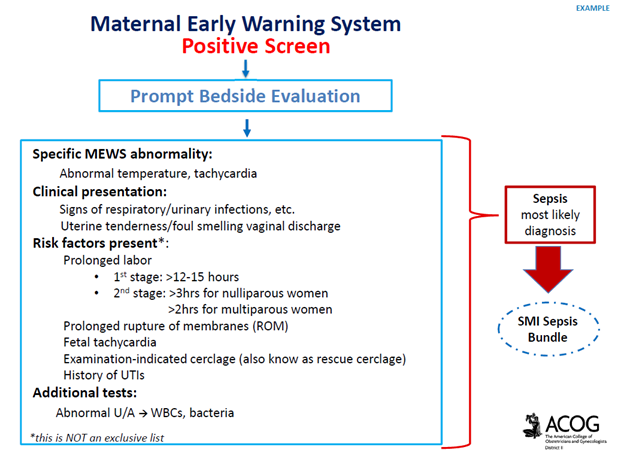

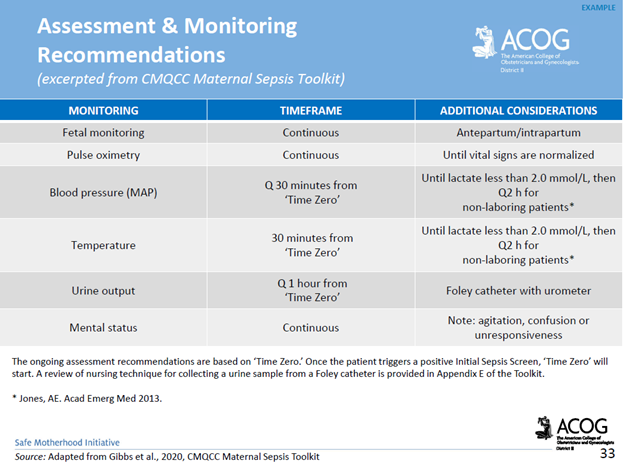

Screening & Diagnostic Criteria: The use of a maternal early warning system (MEWS) is recommended. This is a set of specific vital sign, and physical exam findings that prompt a bedside evaluation and/or work-up (see ACOG’s MEWS example below)

Complications of Maternal Sepsis: Complications include, but are not limited to, maternal death, fetal death (pregnancy loss), preterm premature rupture of membranes, preterm labor and birth, preterm delivery complications of the newborn, lower newborn weight, cerebral white matter damage, cerebral palsy, and neurodevelopmental delay.

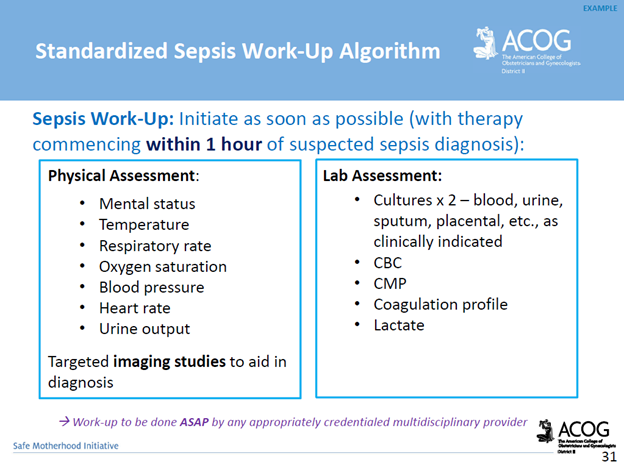

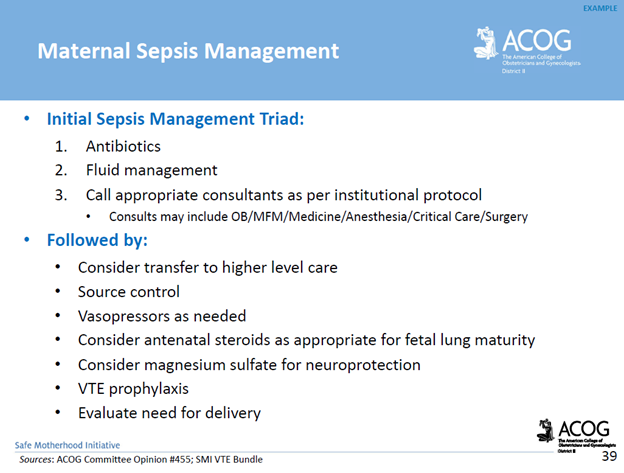

Management Recommendations: Survivability requires early detection, prompt recognition of the source of infection, and targeted therapy.

*Delayed antibiotics > 1 hour = increased mortality

How The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ (ACOG) Safe Motherhood Initiative (SMI) Sepsis Bundle Reduces Maternal Morbidity: The SMI is a collaborative initiative between ACOG and NYSDOH to improve patient safety and raise awareness about risk factors that contribute towards maternal morbidity & mortality. The SMI supports provider readiness, and recognition through the availability of education, standardized sepsis work-up criteria and diagnostic tools. The SMI supports timely provider response, and reporting by the availability of a standardized sepsis management algorithm, recommended criteria for consultation, and transfer to a higher level of care, and case debriefing tools.

Resources:

ACNM, 2018. Recognition and Treatment of Sepsis in Pregnancy

ACOG, 2020. Maternal Safety Bundle for Sepsis in Pregnancy

JAMA Network Open. 2021;4(9): Perinatal Outcomes Among Patients with Sepsis During Pregnancy

Kabiri D, Prus D, Alter R, Gordon G, Porat S, Ezra Y. 2022. Case report: An unusual presentation of puerperal sepsis. Front Med 15:9.

P.S. Comment and Share: What is your experience with maternal sepsis?

If you are in need of a medical legal expert specific to a maternal sepsis case, contact Barber Medical Legal Nurse Consulting, LLC. Email: Contact@barbermedicallegalnurse.com

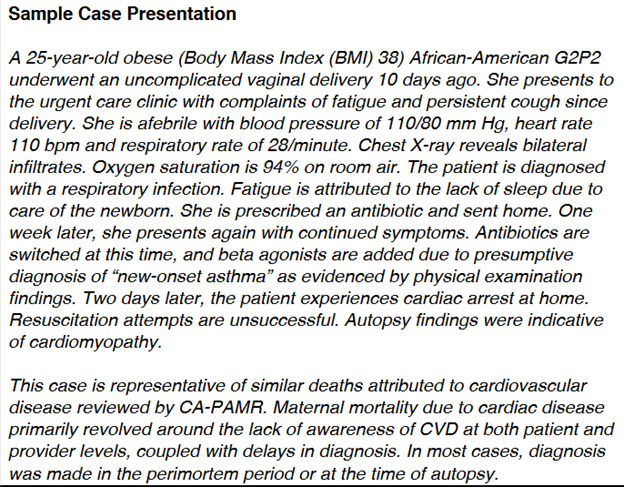

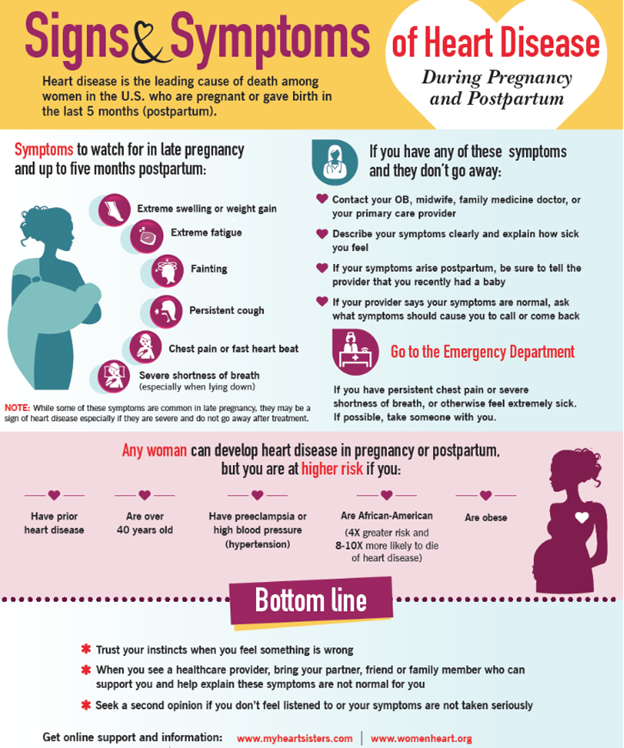

In this blog, I’ll be reviewing the incidence of cardiovascular disease (CVD) in pregnancy, and postpartum. Additionally, I’ll present a case presentation in an effort for the reader to reflect on the learned knowledge from the blog post in the context of the presented case. I’ll also address the challenges associated with diagnosing CVD in pregnancy, and postpartum, while highlighting the signs, and symptoms as well as risk factors for CVD. In closing, I’ll conclude with key takeaways.

Incidence: Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is one of the leading causes of maternal mortality in the United States accounting for >33% of all pregnancy-related deaths in the U.S. One of every three intensive care admissions in pregnancy, and the postpartum period are related to CVD. CVD is under-recognized in pregnant, and postpartum women with rates higher among African-American women.

It’s estimated that 25% of deaths caused by cardiovascular disease in pregnancy or during the postpartum period may have been prevented if CVD had been diagnosed earlier. Only a small fraction of women who die from CVD have a known diagnosis of CVD prior to death. The majority of women who die from CVD present with symptoms either during pregnancy or after childbirth

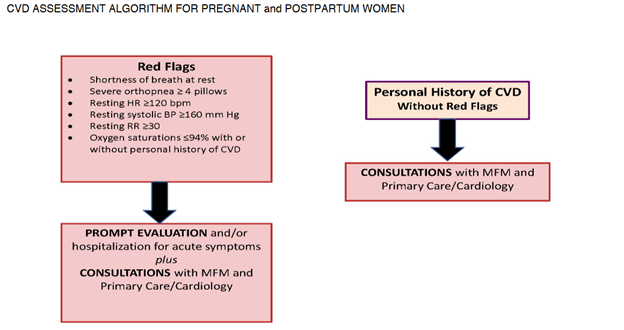

CMQCC, 2017. CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE IN PREGNANCY AND POSTPARTUM TOOLKIT

Diagnostic Challenges and Signs/Symptoms: Signs, and symptoms of normal pregnancy, and postpartum mirror CVD making it difficult to diagnose. This is due to the normal physiological changes that occur in pregnancy, and the postpartum period. However, a diagnosis of CVD should be suspected when symptoms are severe (see red flags below) with vital sign abnormalities, and underlying risk factors. Having an increased awareness of the prevalence of CVD, and a high index of suspicion, along with preconception counseling, and referral to a higher level of care can prevent adverse maternal outcomes.

CMQCC, 2017. CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE IN PREGNANCY AND POSTPARTUM TOOLKIT

Risk Factors: Risk factors for the development of CVD in pregnancy, and postpartum include polycystic ovary syndrome, infertility, adverse pregnancy outcomes such as hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, gestational diabetes, preterm delivery, and intrauterine growth restriction.

Key Takeaways:

References:

ACOG, 2019. Pregnancy and heart disease.

AHA, 2020. Cardiac arrest in pregnancy in-hospital ACLS algorithm.

AWHONN, 2023. Obstetric patient safety ob emergencies workshop, 3rd ed.

CMQCC, 2017. Cardiovascular disease in pregnancy and postpartum toolkit.

P.S. COMMENT AND SHARE: What is your experience with cardiovascular disease in pregnancy or in the postpartum period? Have you been involved in an adverse outcome as a result of a CVD diagnosis, or failed diagnosis?

Learning From Lawsuits: Verdict Review – Wrongful Maternal Death Case Involving Preeclampsia,

Preeclampsia Case Review

In an effort to help improve maternal health outcomes, we need to be open minded to learning from lawsuits, and implementing necessary change in an effort to prevent recurrence.

In this blog, I’ll be discussing preeclampsia. I’ll review symptoms of preeclampsia, as well as the incidence, and I’ll introduce a lawsuit involving a maternal death as a result of severe preeclampsia. In closing, I’ll identify key clinical takeaways regarding the standard of care specific to timely diagnosis, treatment, and follow up when caring for women with a diagnosis of preeclampsia.

Preeclampsia Definition: Preeclampsia is a disorder of pregnancy associated with a new onset of hypertension, which can affect every body organ. The onset occurs after 20 weeks of pregnancy; It can also develop in the weeks after childbirth. Symptoms can include:

A woman with preeclampsia whose condition is worsening can develop “severe features”. Severe features include:

Incidence: preeclampsia complicates up to 8% of pregnancies globally.

Case Facts: The plaintiff’s decedent was a 34-year-old who was hospitalized at Samaritan North Hospital due to preeclampsia at 36 weeks gestation. The patient was under the care of a board-certified family physician who had minor privileges to deliver uncomplicated pregnancies. The family physician saw the patient in her office for a routine prenatal visit. At that time, the patient reported a headache and cough. The patient’s blood pressure was increased from her baseline to 130/90, and she had a 6.8-pound weight gain since her last visit. The patient was advised to return to the office in two weeks. Two days later, the patient contacted her family physician, and reported vaginal bleeding and a headache. The family physician instructed the patient to go to the emergency room. The patient was subsequently admitted with a diagnosis of a potential placental abruption. An ultrasound revealed oligohydramnios (decreased amniotic fluid for gestational age), intrauterine growth restriction, and a Grade II placenta (some placental calcification/hyperechoic areas). During the patients admission she experienced repeated high blood pressures, headaches, variable, and late decelerations, an abnormal D-Dimer reading, and a drop in her platelet count. Five days later, the patient was discharged from the hospital and advised to go to M. Valley Hospital to obtain an ultrasound. That same evening, the patient called the family physician, and reported vomiting, abdominal pain, and headaches. The family physician reportedly instructed the patient to call her back in one hour which she did, and was told to go to the hospital. Upon arrival to the hospital the patients’ blood pressure was 128/103, and 155/100. The patient was allegedly grimacing, complaining of a headache, was vomiting and had facial edema. The family physician ordered the patient to be admitted for observation. Approximately six hours following the patients arrival to the hospital, she was found with her head hanging over the bed, having vomited, and in an obtunded state. The emergency response team was called, and an obstetrician who was physically on the unit was called to evaluate the patient. The obstetrician ordered magnesium sulfate, and hydralazine. The obstetrician diagnosed the patient with eclampsia, and immediately transported her to the operating room for delivery of her baby boy by cesarean section. The patient remained unresponsive. A CT scan confirmed a massive intracranial hemorrhage. A brain scan was subsequently performed which showed lack of brain flow, and the patient was pronounced dead.

Plaintiff’s Allegations: The plaintiffs’ counsel contended that the family physician egregiously deviated from the accepted standards of medical care. The lawsuit further claimed that the family physician materially misrepresented to the patient that she was experienced and trained in the treatment of all her obstetrical conditions, and fraudulently concealed from her that her ability to practice obstetrics was restricted to minor obstetrics in accordance with the Samaritan North Hospital policy. The lawsuit also claimed that the family physician was guilty of constructive fraud, was inadequately trained and inexperienced to treat the patient, and abandoned her patient by failing to adequately diagnose, and treat her condition or refer her to an obstetrician who could provide treatment to her.

Defendant’s Allegations: The defense argued that the family physician met the standard of care applicable in this case. The defense pointed to the fact that the family physician was credentialed to practice obstetrics at Samaritan Hospital. Also, the defense contended that the patient’s blood pressures were never sustained, and never reached a level that would require a consult with an obstetrician before the event occurred. The defense maintained that the family physician did consult with a board-certified obstetrician, and maternal fetal medicine specialist who ordered continuous antepartum testing, and induction at 39 weeks, and that the family physician appropriately instructed the patient to return to the hospital for monitoring. The defense argued that the patients complications, and death were unforeseeable. The defense argued that the patient never had an eclamptic seizure, and that she never met criteria for preeclampsia. Additionally, the defense argued that the evidence demonstrated that, more likely than not, this was a ruptured aneurysm in a patient with a family history of stroke.

Physical Injuries Claimed by Plaintiff: The patient allegedly died from complications of preeclampsia that caused a major intracranial hemorrhage.

Gross Verdict (Award): The jury found that the negligence of the family physician, and the private practice was a direct, and proximate cause of the patients death. The jury awarded compensatory damages of $6,067,830.10, which included loss of support from earning capacity of the patient; loss of services; loss of society including companionship, consortium, care, assistance, attention, protection, advise, guidance, counsel, instruction, training, and education suffered by the surviving spouse, children, parents, and next of kin; mental anguish; and reasonable funeral and burial expenses. The award was reduced to $900,000 pursuant to a high/low agreement.

Standard of Care Takeaways:

Resources:

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, (2020). Gestational hypertension & preeclampsia. Practice Bulletin #222.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. (n.d.). Safe motherhood initiative. Retrieved March 8, 2023, from https://www.acog.org/community/districts-and-sections/district-ii/programs-and-resources/safe-motherhood-initiative

California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative. Retrieved December 17, 2023, from https://www.cmqcc.org/

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System. Retrieved December 27, 2023, from https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternal-mortality/pregnancy-mortality-surveillance-system.htm

Collier A.Y., Molina R.L. (2019). Maternal Mortality in the United States: Updates on Trends, Causes, and Solutions

P.S. COMMENT AND SHARE: Have you had a case theme centered around diagnosis, and/or management of preeclampsia? What were some of the case facts? How did the case facts impact the case outcome?

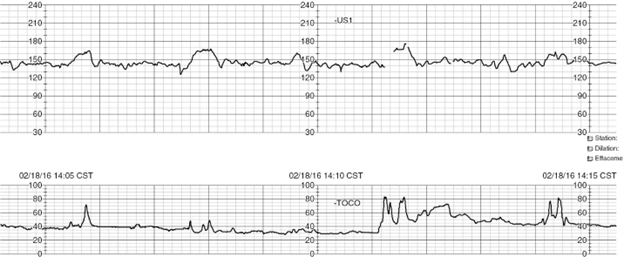

Case Review: 21-year-old primiparous (first pregnancy) at 35+4 weeks gestational age presents to labor and delivery triage status post a motor vehicle accident (MVA) 4 hours prior to arrival. Patient reports occasional mild uterine contractions on arrival. Denies vaginal bleeding, or leaking of fluid. Reports decreased fetal movement since the MVA. Obstetrical history is significant for anemia, and O negative blood type.

1:30pm: RN progress note – occasional mild uterine contractions. Abdomen soft, non-tender. FHR 125 with moderate variability. Occasional accelerations. Absent decelerations. Occasional mild uterine contractions. Category I fetal heart rate (FHR) tracing reported to attending Ob/Gyn via telephone (in reference to above tracing).

5:30pm: RN progress note – Telephone report provided to Dr. Z. Category I tracing. Reassuring maternal, and fetal status. Rhogam administered. Orders received to discharge patient home with follow up in office as previously scheduled.

11:30pm: Patient returned to labor and delivery triage with onset of painful uterine contractions, and vaginal bleeding. Uncertain if perceiving fetal movement. Abdomen rigid, and tender to touch. Fetal heart tones absent. Intrauterine fetal demise confirmed via bedside obstetrical ultrasound. Patient desires primary cesarean section. Placenta abruption confirmed at delivery.

Sinusoidal FHR Pattern: A sinusoidal FHR pattern is uncommon. The smooth, sine wave-like undulating pattern in the FHR baseline serves to distinguish this pattern from variability. In the presence of a sinusoidal FHR pattern, there is a cycle frequency of 3 to 5 per minute that persists for 20 minutes. A sinusoidal FHR pattern can be misinterpreted as moderate variability. This misinterpretation puts the team (including the patient, and her family) at risk for misdiagnosis, and mismanagement.

An effective way to distinguish FHR variability from the sinusoidal pattern is by recognizing that variability is defined as fluctuations in the baseline that are irregular in amplitude, and frequency. By contrast, the sinusoidal pattern is characterized by fluctuations in the baseline that are regular in amplitude, and frequency. Spontaneous accelerations are absent, nor are they elicited in response to uterine contractions, fetal movement, or stimulation (i.e., digital scalp stimulation, vibroacoustic stimulation).

Causes: Causes of a sinusoidal FHR pattern can include fetal anemia as a result of Rh isoimmunization (i.e., the mother’s blood protein is incompatible with the fetus’s in the case of a maternal Rh negative [O negative] blood type), fetal maternal hemorrhage (i.e., placenta abruption), twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome, ruptured vasa previa, and fetal intracranial hemorrhage. Other fetal conditions that have been reported to be associated with a sinusoidal FHR pattern include fetal hypoxia or asphyxia, fetal infection, fetal cardiac anomalies, and gastroschisis.

Pseudosinusoidal, or medication induced sinusoidal can occur after the administration of some opioids, fetal sleep cycles, or rhythmical movements of the fetal mouth. These events are of short duration, preceded, and followed by an FHR with normal characteristics. These short periods of sinusoidal appearing patterns do not require treatment.

Significance / Management: A sinusoidal FHR pattern is associated with an increased risk for fetal acidemia at the time of observation. This pattern is to be considered a Category III (abnormal), which requires immediate evaluation, intrauterine resuscitation, and expedited birth if unresolved.

References

Lydon, and Wisner, (2021). Fetal Heart Monitoring Principles and Practices

Miller et al., (2022). Mosby’s Pocket Guide to Fetal Monitoring

Simpson et al., (2021). Perinatal Nursing

P.S. COMMENT AND SHARE: What is your experience reviewing a case involving a sinusoidal FHR pattern? Was the abnormal pattern identified timely? Was the pattern misinterpreted as moderate variability? What was the neonatal outcome?

In this blog, I’ll be reviewing a maternal wrongful death case involving obstetrical hemorrhage. I’ll identify how to diagnose obstetrical hemorrhage, and review the incidence of obstetrical hemorrhage within the United States. Following a review of case facts, I’ll highlight key standard of care takeaways that support obstetrical hemorrhage prevention, early identification, and intervention. The provided takeaways are evidence based practices which serve to reduce the incidence of maternal morbidity, and mortality associated with obstetrical hemorrhage.

Definition: Obstetrical hemorrhage is defined as a cumulative blood loss of greater than or equal to 1,000 ml. of blood loss accompanied by signs or symptoms of hypovolemia within 24 hours after childbirth, regardless of the mode of delivery (AGOG, 2021).

Incidence: Obstetrical hemorrhage remains one of the leading causes of pregnancy-related deaths worldwide. In the U.S., during 2017 – 2019, obstetrical hemorrhage accounted for 12.1% of the total pregnancy-related deaths (CDC, 2023).

Case Facts: A 36-year-old mother experienced profound uterine bleeding immediately after cesarean section for a twin delivery. The patient was transferred to the post anesthesia care unit (PACU) where she continued to have severe bleeding, vital sign instability, and experienced hemorrhagic shock. The patient received fluid resuscitation with blood products, and intravenous fluids. Blood products were not promptly available. The patient was transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) where her vital signs continued to worsen. The Obstetrician urged for an immediate hysterectomy. After the patient was transferred to the ICU, the anesthesiologist left the hospital for another case at a different hospital, and there was no anesthesiologist available. A hysterectomy was eventually performed. Due to the postpartum bleeding, and insufficient fluid resuscitation with blood products, the patient developed disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC). The patient was pronounced dead shortly after the DIC diagnosis was made. The anesthesiologist settled out. The case continued to trial against the hospital and Obstetrician.

Plaintiff’s Allegations: The plaintiffs’ counsel contended the patient needed operative intervention much sooner to stop the uterine bleeding. Plaintiffs’ counsel also contended the hospital blood bank did not promptly deliver the needed blood products. Lastly, the hospital failed to perform lab tests to assess the extent of the patients bleeding.

Defendant’s Allegations: The hospital contended the death was due to the negligence of the other physicians, including the anesthesiologist, for failing to promptly respond to, and manage the evolving shock.

Physical Injuries Claimed by Plaintiff: Death; loss of love, companionship, comfort, care, assistance, protection, affection, society, moral support; loss of training and guidance; loss of financial support; the reasonable value of household services.

Gross Verdict (Award): $10,850,000 (100% against the hospital. The obstetrician received a 12-0 defense verdict)

Standard of Care Takeaways:

Closing Remarks: Professional organizational standards exist specific to prevention, early recognition, and timely treatment of obstetrical hemorrhage. Obstetrical risk reduction strategies should involve adoption of obstetrical hemorrhage safety bundles, perinatal quality review processes, as well as multidisciplinary data review by means of audit and feedback methodologies.

Resources:

AGOC, 2021. Postpartum Hemorrhage

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, (2023). Healthy People 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/healthy_people/hp2020.htm

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, (2023).Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System. https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternal-mortality/pregnancy-mortality-surveillance-system.htm

The Joint Commission, 2023). R3 Report Issue 24: PC Standards for Maternal Safety. https://www.jointcommission.org/standards/r3-report/r3-report-issue-24-pc-standards-for-maternal-safety/#.ZAdWsB_MJPY

P.S. COMMENT AND SHARE: Have you been involved in a maternal wrongful death case involving obstetrical hemorrhage? What was the case theme? What were strengths, and weaknesses of the case?

Barber Medical legal Nurse Consulting, LLC is available to support medical record review of obstetrical care involving a hemorrhage, perinatal quality consults, and obstetrical hemorrhage education. Email: Contact@barbermedicallegalnurse.com.