Learning From Lawsuits: Verdict Review – Wrongful Maternal Death Case Involving Preeclampsia,

Maternal Health Awareness

Preeclampsia Case Review

In an effort to help improve maternal health outcomes, we need to be open minded to learning from lawsuits, and implementing necessary change in an effort to prevent recurrence.

In this blog, I’ll be discussing preeclampsia. I’ll review symptoms of preeclampsia, as well as the incidence, and I’ll introduce a lawsuit involving a maternal death as a result of severe preeclampsia. In closing, I’ll identify key clinical takeaways regarding the standard of care specific to timely diagnosis, treatment, and follow up when caring for women with a diagnosis of preeclampsia.

Preeclampsia Definition: Preeclampsia is a disorder of pregnancy associated with a new onset of hypertension, which can affect every body organ. The onset occurs after 20 weeks of pregnancy; It can also develop in the weeks after childbirth. Symptoms can include:

- swelling of the face or hands

- headache that will not go away with rest, hydration, Tylenol

- seeing spots or changes in eyesight

- pain in the upper abdomen or shoulder

- nausea and vomiting (in the second half of pregnancy)

- sudden weight gain

- difficulty breathing

A woman with preeclampsia whose condition is worsening can develop “severe features”. Severe features include:

- low number of platelets in the blood

- abnormal kidney or liver function

- pain in the upper abdomen

- changes in vision

- fluid in the lungs

- severe headache

- systolic pressure of 160 mm Hg or higher or diastolic pressure of 110 mm Hg or higher

Incidence: preeclampsia complicates up to 8% of pregnancies globally.

- Annually, 16% of global pregnancy related deaths can be attributed to hypertensive disorders.

- In the U.S., between 2017-2019, hypertensive disorders caused 6.3% of pregnancy related deaths.

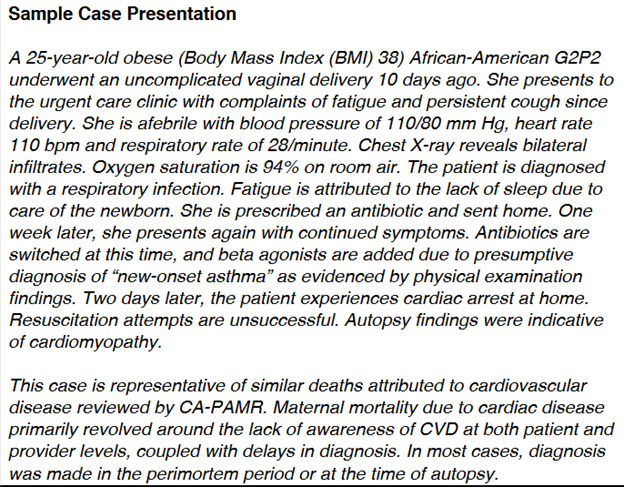

Case Facts: The plaintiff’s decedent was a 34-year-old who was hospitalized at Samaritan North Hospital due to preeclampsia at 36 weeks gestation. The patient was under the care of a board-certified family physician who had minor privileges to deliver uncomplicated pregnancies. The family physician saw the patient in her office for a routine prenatal visit. At that time, the patient reported a headache and cough. The patient’s blood pressure was increased from her baseline to 130/90, and she had a 6.8-pound weight gain since her last visit. The patient was advised to return to the office in two weeks. Two days later, the patient contacted her family physician, and reported vaginal bleeding and a headache. The family physician instructed the patient to go to the emergency room. The patient was subsequently admitted with a diagnosis of a potential placental abruption. An ultrasound revealed oligohydramnios (decreased amniotic fluid for gestational age), intrauterine growth restriction, and a Grade II placenta (some placental calcification/hyperechoic areas). During the patients admission she experienced repeated high blood pressures, headaches, variable, and late decelerations, an abnormal D-Dimer reading, and a drop in her platelet count. Five days later, the patient was discharged from the hospital and advised to go to M. Valley Hospital to obtain an ultrasound. That same evening, the patient called the family physician, and reported vomiting, abdominal pain, and headaches. The family physician reportedly instructed the patient to call her back in one hour which she did, and was told to go to the hospital. Upon arrival to the hospital the patients’ blood pressure was 128/103, and 155/100. The patient was allegedly grimacing, complaining of a headache, was vomiting and had facial edema. The family physician ordered the patient to be admitted for observation. Approximately six hours following the patients arrival to the hospital, she was found with her head hanging over the bed, having vomited, and in an obtunded state. The emergency response team was called, and an obstetrician who was physically on the unit was called to evaluate the patient. The obstetrician ordered magnesium sulfate, and hydralazine. The obstetrician diagnosed the patient with eclampsia, and immediately transported her to the operating room for delivery of her baby boy by cesarean section. The patient remained unresponsive. A CT scan confirmed a massive intracranial hemorrhage. A brain scan was subsequently performed which showed lack of brain flow, and the patient was pronounced dead.

Plaintiff’s Allegations: The plaintiffs’ counsel contended that the family physician egregiously deviated from the accepted standards of medical care. The lawsuit further claimed that the family physician materially misrepresented to the patient that she was experienced and trained in the treatment of all her obstetrical conditions, and fraudulently concealed from her that her ability to practice obstetrics was restricted to minor obstetrics in accordance with the Samaritan North Hospital policy. The lawsuit also claimed that the family physician was guilty of constructive fraud, was inadequately trained and inexperienced to treat the patient, and abandoned her patient by failing to adequately diagnose, and treat her condition or refer her to an obstetrician who could provide treatment to her.

Defendant’s Allegations: The defense argued that the family physician met the standard of care applicable in this case. The defense pointed to the fact that the family physician was credentialed to practice obstetrics at Samaritan Hospital. Also, the defense contended that the patient’s blood pressures were never sustained, and never reached a level that would require a consult with an obstetrician before the event occurred. The defense maintained that the family physician did consult with a board-certified obstetrician, and maternal fetal medicine specialist who ordered continuous antepartum testing, and induction at 39 weeks, and that the family physician appropriately instructed the patient to return to the hospital for monitoring. The defense argued that the patients complications, and death were unforeseeable. The defense argued that the patient never had an eclamptic seizure, and that she never met criteria for preeclampsia. Additionally, the defense argued that the evidence demonstrated that, more likely than not, this was a ruptured aneurysm in a patient with a family history of stroke.

Physical Injuries Claimed by Plaintiff: The patient allegedly died from complications of preeclampsia that caused a major intracranial hemorrhage.

Gross Verdict (Award): The jury found that the negligence of the family physician, and the private practice was a direct, and proximate cause of the patients death. The jury awarded compensatory damages of $6,067,830.10, which included loss of support from earning capacity of the patient; loss of services; loss of society including companionship, consortium, care, assistance, attention, protection, advise, guidance, counsel, instruction, training, and education suffered by the surviving spouse, children, parents, and next of kin; mental anguish; and reasonable funeral and burial expenses. The award was reduced to $900,000 pursuant to a high/low agreement.

Standard of Care Takeaways:

- Early Recognition and Management: Health care systems responsible for rendering care to pregnant and postpartum persons should develop procedures for (re)measuring blood pressure, and integrate standardized criteria for the diagnosis, and management of preeclampsia, and severe hypertension.

- Education: Role specific multidisciplinary education, simulation training, and team de-briefing should be required for all members responsible for caring for obstetrical, and postpartum patients. Care areas should include labor and delivery, anesthesia, emergency department, and intensive care unit.

- Quality Improvement: Organizational review of severe hypertension/preeclampsia cases should occur as part of a quality improvement process. Additionally, printed patient and family education should be disseminated focusing on risk factors for severe hypertension/preeclampsia, as well as signs and symptoms to report.

- Maternal Safety Bundles: Multiple organizations (i.e., ACOG, AWHONN, CDC, CMQCC, NIH) have maternal safety bundles that focus on prevention, early identification, and early treatment of preeclampsia in an effort to reduce maternal mortality. Organizations are encouraged to integrate such safety bundles into their policies and procedures.

Resources:

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, (2020). Gestational hypertension & preeclampsia. Practice Bulletin #222.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. (n.d.). Safe motherhood initiative. Retrieved March 8, 2023, from https://www.acog.org/community/districts-and-sections/district-ii/programs-and-resources/safe-motherhood-initiative

California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative. Retrieved December 17, 2023, from https://www.cmqcc.org/

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System. Retrieved December 27, 2023, from https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternal-mortality/pregnancy-mortality-surveillance-system.htm

Collier A.Y., Molina R.L. (2019). Maternal Mortality in the United States: Updates on Trends, Causes, and Solutions

P.S. COMMENT AND SHARE: Have you had a case theme centered around diagnosis, and/or management of preeclampsia? What were some of the case facts? How did the case facts impact the case outcome?