CASE REVIEW: UTERINE ACTIVITY – ASSESSMENT, DOCUMENTATION, MANAGEMENT, AND IMPACT ON THE FETUS

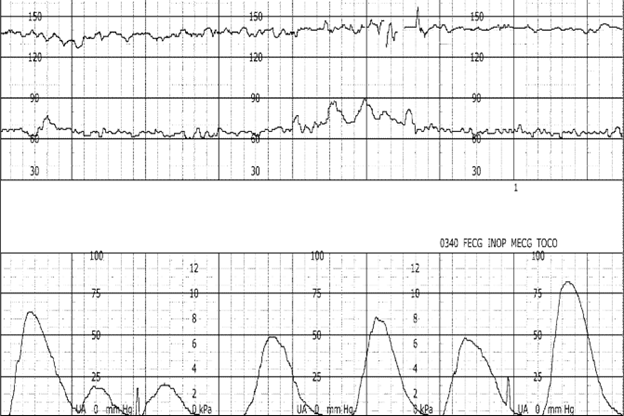

In this blog, I’ll present a segment of an electronic fetal monitor (EFM) tracing. Following review of the tracing, and a brief Q&A, I’ll be highlighting the case theme affiliated with the presented EFM tracing. Additionally, I’ll provide plaintiff allegations, as well as defenses contended. Review of the standard of care specific to uterine activity evaluation, and management will be provided. In closing, the impact excessive uterine activity has on fetal well-being will be discussed.

Ob Provider Progress Note:

2/12/22 0340: vaginal exam 2-3/50/-1. artificial rupture of membranes, clear fluid. fetal heart rate reassuring. pitocin @ 7mU/min.

Nurses Note:

2/12/22 0345: Ob provider at bedside. vaginal exam performed. strip reviewed. baseline fetal heart rate 140, minimal variability, absent accelerations, intermittent late decelerations.

Q: What assessment is missing from the above documentation?

A: Assessment of uterine activity

Litigation Case Theme: Failure of the perinatal team to identify, and act on a category II FHR tracing in the presence of uterine tachysystole, and excessive uterine activity resulting in permanent neurological injuries in the infant.

Plaintiff Allegations:

- Failure of the perinatal team to assess and intervene

- Failure of the perinatal team to recognize a non-reassuring FHR pattern, and excessive uterine activity

- Inappropriate oxytocin management

- Failure to initiate intrauterine resuscitation, and interventions in response to excessive uterine activity

Defenses:

- The standard of care was adhered to

- Documentation reflected prompt, and appropriate actions by the perinatal team

- Electronic fetal monitoring cannot be used as a diagnostic tool; therefore, birth injury cannot be attributed solely to FHR interpretation

- The fetal injury likely occurred during the antenatal period; therefore, actions during labor and delivery had no impact on the outcome

Standard of Care: the evaluation of uterine activity must occur, and is equally as relevant as the assessment of the fetal heart rate.

Complete assessment of uterine activity: components of uterine activity assessment, and documentation include –

- uterine contraction frequency: ranges from 2 – 5 per 10 minutes.

- duration of uterine contractions: ranges from 45 – 80 seconds.

- strength or intensity of uterine contractions: 40 – 70 mm Hg (millimeters of mercury) in the first stage of labor. May rise to >80 mm Hg in the second stage of labor. Contractions palpated as “mild” would peak at <50 mm Hg if measured internally. Contractions palpated as “moderate” or greater would peak at 50 mm Hg or greater if measured internally.

- resting tone of uterus: the average resting tone during labor is 10 mm Hg. If assessment is performed by palpation, assessment should palpate as “soft”.

- relaxation time between uterine contractions: this is usually 60 seconds or more in the first stage of labor, and 45 seconds or more in the second stage.

- Montevideo units (MVUs): assessed and documented if an intrauterine pressure catheter (IUPC) is in place. MVUs range from 100 – 250 MVUs in the first stage of labor. MVUs may rise to 300 – 400 MVUs in the second stage of labor.

What is excessive uterine activity? uterine tachysystole is defined as greater than five uterine contractions in 10 minutes, averaged over 30 minutes.

Tachysystole should be further qualified by the presence of absence of FHR decelerations, and applies to spontaneous and stimulated labors.

All other parameters, as identified above (duration, intensity, resting tone, and relaxation time), should be included in the evaluation.

Management of excessive uterine activity: management of excessive uterine activity should not be based on the presence or absence of FHR changes.

The goal of management is to identify, and promote normal uterine activity, and correct the underlying cause of any type of excessive uterine activity.

- maternal position change to side-lying

- administration of an intravenous fluid bolus

- removal of cervical ripening agents, or decrease or discontinuation of oxytocin

- use of a tocolytic (e.g., terbutaline) if the above interventions were ineffective, or the excessive uterine activity occurs in the presence of FHR changes indicative of interrupted fetal oxygenation

Excessive uterine activity should trigger interventions, regardless of FHR status.

Fetal effects on FHR from excessive uterine activity: excessive uterine activity can have an adverse effect on fetal oxygenation, and the fetal acid-base status. Excessive uterine activity can result in decreased fetal cerebral oxygen saturation, as well as fetal acidemia. Excessive uterine activity can result in birth injuries, specifically, hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy, and subsequent cerebral palsy.

Conclusion: The assessment of uterine activity during labor is crucial, and is considered a patient safety issue. Applying known parameters to the assessment of uterine activity influences management decisions, forms the basis of safe use of labor stimulants, and provides a means of defining excessive uterine activity among the multidisciplinary perinatal team.

Resources:

AAP, ACOG (2017). Guidelines for Perinatal Care.

ACOG (2009). Induction of Labor.

ACOG (2010). Intrapartum Fetal Heart Rate Tracings.

AWHONN (2021). Perinatal Nursing.

AWHONN (2022). Intermediate Fetal Monitoring Course.

Miller et al., (2022). Pocket Guide to Fetal Monitoring.

P.S. Comment and Share: What is your experience working with a case theme centered around excessive uterine activity? What were some strengths? What were some challenges?