MATERNAL SEPSIS: CASE STUDY AND REVIEW

In this blog, I’ll be introducing a maternal sepsis case study, followed by supportive content to enhance the readers understanding of the incidence of maternal sepsis in the U.S., causes, risk factors, and complications that can occur as a result of maternal sepsis. I’ll provide information on the recommended screening, diagnostic criteria, as well as assessment, and treatment recommendations.

Case Study: A 38-year-old woman, gravida 6 para 5, with an unremarkable past medical history presented to labor and delivery in active labor at 39 weeks of gestation and delivered vaginally shortly thereafter. Delivery was uneventful, without regional anesthesia and without perineal tears nor other complications. Twenty-four hours after delivery, the patient developed isolated left lower quadrant pain. Physical examination, abdominal ultrasound, and laboratory tests including complete blood count and basic metabolic panel were unremarkable, and the pain subsided after a bowel movement. On the following day, abdominal pain worsened, while the patient remained afebrile and was hemodynamically stable. Clinical assessment and physical examination of the pelvis and abdomen by the gynecological and surgical teams were unremarkable and revealed no acute distress; the abdomen was soft and non-tender on palpation, and bowel sounds were normal in all four quadrants. Notably, there was a significant discrepancy between the symptoms (referred abdominal pain) and the objective clinical findings. An abdominal and pelvic CT scan demonstrated normal post-partum uterus, endometrium and pelvic organs without signs of acute pathology. A large fecal burden throughout the colon was seen, suggesting possible constipation. Subsequently, 60 h after birth, her clinical condition deteriorated as the patient developed tachycardia with 130 beats per minute, tachypnea with 20 breaths per minute, and blood pressure of 103/65 mmHg. Laboratory values included a white blood cell count of 1.5 × 109/L and C-Reactive Protein (CRP) of 27.1 mg/dl and Lactic acid of 4.05 mmol/L. Creatinine, liver-function tests, and electrolytes were within the normal range. Due to a high clinical suspicion of puerperal sepsis at this point, a wide-spectrum antibiotic regime of ampicillin, clindamycin and gentamicin was initiated, and the patient was transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU). Shortly afterward, the patient became hemodynamically and respiratorily unstable and required sedation, mechanical ventilation, and the use of inotropes to maintain adequate blood pressure. Laboratory results revealed worsening leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, and lactic acidosis. A post-contrast computed tomography scan showed an enlarged uterus with abundant periovarian and peritoneal fluid. Since the presence of pus in the abdomen was suspected and due to the severe clinical deterioration, an emergency exploratory laparotomy was executed, during which 600 ml of thick yellowish-white abdominal fluid was aspirated. The uterus and both ovaries were swollen, necrotic, and covered with fibrin, therefore a total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy were performed. Ovarian preservation was not possible because of severe necrosis. Gross findings of the post-operative pathological specimen showed an ischemic and partially necrotic uterus, while microscopic examination of the uterus revealed a severe acute inflammatory process with necrotic myometrium and bacterial colonies, confirmed later to be Streptococcus pyogenes on blood-agar medium culture. Post-operatively, the patient underwent a prolonged recovery period and was discharged without any further obstetrical or gynecological complications (Kabiri D, et al., 2022. Case report: An unusual presentation of puerperal sepsis. Front Med).

What is Maternal Sepsis: Maternal sepsis is a life-threatening condition defined as organ dysfunction resulting from infection during pregnancy, childbirth, post-abortion, or postpartum period.

The most common pathogens that cause maternal sepsis include Streptococcus pyogenes, Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, Group B Streptococcus, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), Clostridium septicum, and Morganella morganii.

Clinical Presentation: The normal changes of pregnancy complicate identification, and treatment of maternal sepsis. Pregnant patients appear clinically well prior to rapid deterioration with the development of septic shock, multiple organ dysfunction syndrome, or death. This is due to pregnancy-specific physiologic, mechanical, and immunological adaptations (JAMA, 2021).

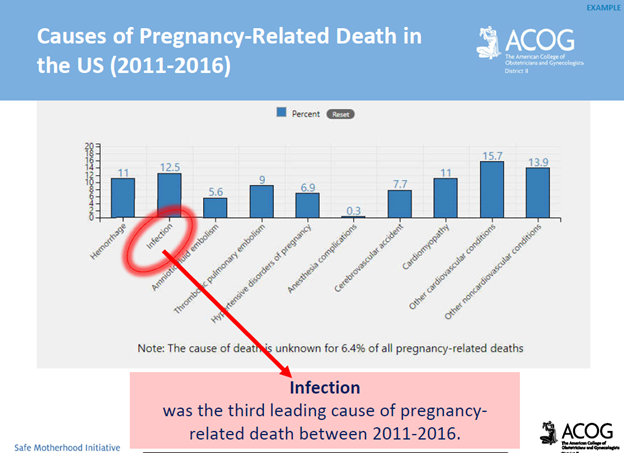

National Statistics: Maternal sepsis is the second leading cause of pregnancy-related death in the United States. Among all pregnancy-related deaths in the U.S., 12.5% are attributed to sepsis (JAMA, 2021). It is estimated that 4 to 10 per 10,000 live births are complicated by maternal sepsis (ACNM, 2018). Rates of pregnancy-associated sepsis are increasing in the U.S., as are rates of sepsis-related maternal deaths.

*Approximately 40% of maternal sepsis cases are preventable with early recognition, early escalation of care, and appropriate antibiotic treatment (Kabiri D. et al. 2022).

Risk Factors: Risk factors for maternal sepsis include advanced maternal age, preterm premature rupture of the membranes (PPROM) and preterm delivery, multiple gestation pregnancies, cesarean delivery, retained products of conception, post-partum hemorrhage, and maternal comorbidities. It’s important to note that maternal sepsis occurs in patients without risk factors.

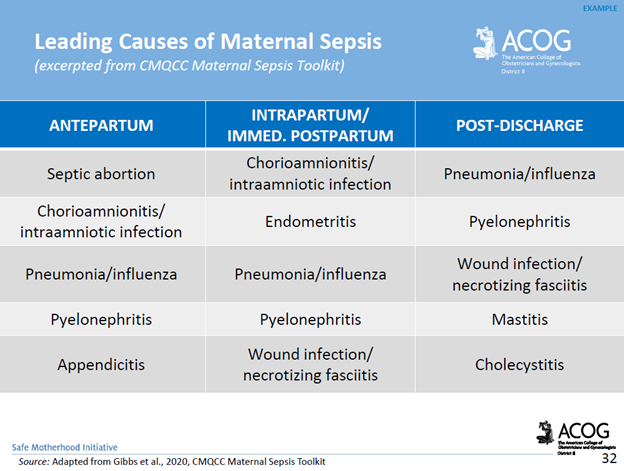

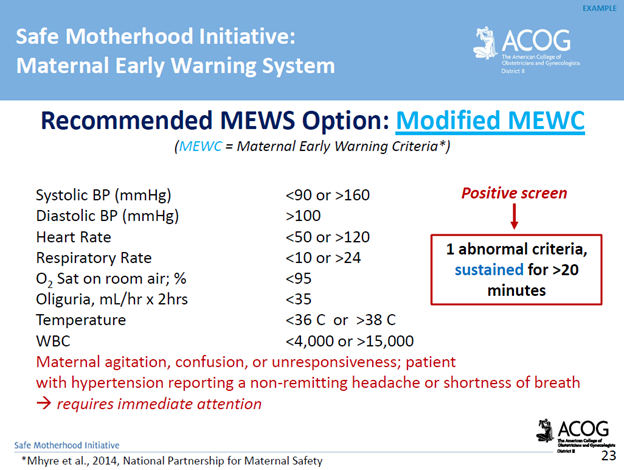

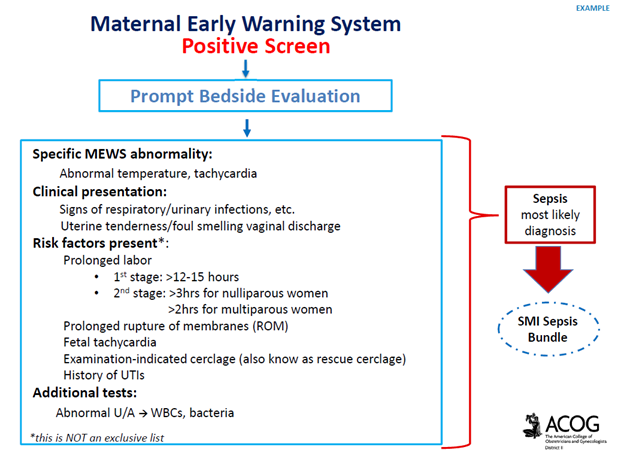

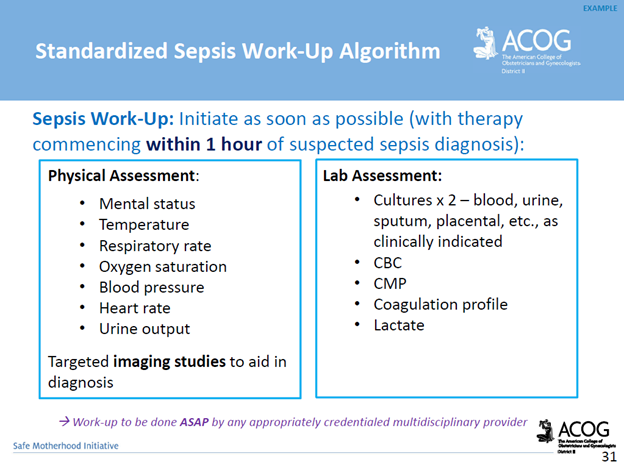

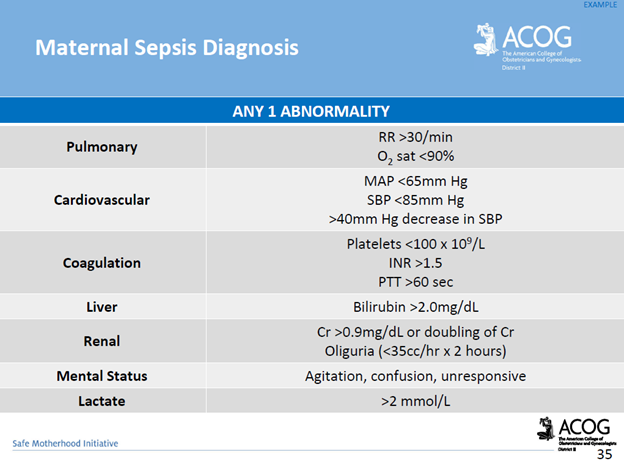

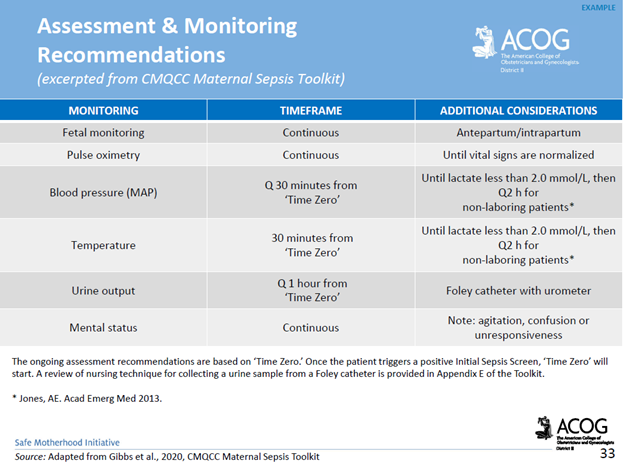

Screening & Diagnostic Criteria: The use of a maternal early warning system (MEWS) is recommended. This is a set of specific vital sign, and physical exam findings that prompt a bedside evaluation and/or work-up (see ACOG’s MEWS example below)

Complications of Maternal Sepsis: Complications include, but are not limited to, maternal death, fetal death (pregnancy loss), preterm premature rupture of membranes, preterm labor and birth, preterm delivery complications of the newborn, lower newborn weight, cerebral white matter damage, cerebral palsy, and neurodevelopmental delay.

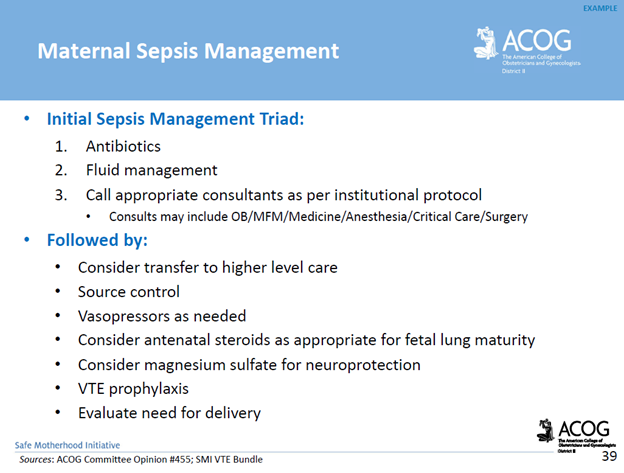

Management Recommendations: Survivability requires early detection, prompt recognition of the source of infection, and targeted therapy.

*Delayed antibiotics > 1 hour = increased mortality

How The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ (ACOG) Safe Motherhood Initiative (SMI) Sepsis Bundle Reduces Maternal Morbidity: The SMI is a collaborative initiative between ACOG and NYSDOH to improve patient safety and raise awareness about risk factors that contribute towards maternal morbidity & mortality. The SMI supports provider readiness, and recognition through the availability of education, standardized sepsis work-up criteria and diagnostic tools. The SMI supports timely provider response, and reporting by the availability of a standardized sepsis management algorithm, recommended criteria for consultation, and transfer to a higher level of care, and case debriefing tools.

Resources:

ACNM, 2018. Recognition and Treatment of Sepsis in Pregnancy

ACOG, 2020. Maternal Safety Bundle for Sepsis in Pregnancy

JAMA Network Open. 2021;4(9): Perinatal Outcomes Among Patients with Sepsis During Pregnancy

Kabiri D, Prus D, Alter R, Gordon G, Porat S, Ezra Y. 2022. Case report: An unusual presentation of puerperal sepsis. Front Med 15:9.

P.S. Comment and Share: What is your experience with maternal sepsis?

If you are in need of a medical legal expert specific to a maternal sepsis case, contact Barber Medical Legal Nurse Consulting, LLC. Email: Contact@barbermedicallegalnurse.com