AVOID COMMUNICATION CONFLICTS THAT COULD COST YOU YOUR CAREER

In this blog I’ll highlight forms of verbal and written communication that are utilized in healthcare settings. Additionally, I’ll provide examples of common communication breakdowns that have been a source of adverse patient outcomes. I’ll close with some suggested risk management strategies.

IMPACT OF COMMUNICATION BREAKDOWNS

Communication breakdowns occur in every area of healthcare, and serve as a common root cause of adverse patient outcomes. The incurred cost of liability related to communication breakdowns is more than one and a half times greater than the overall average total incurred for all nursing professional liability claims. Of 498 closed malpractice claims reviewed, communication failures were identified in half of the claims. Communication errors that involved a failed hand-off report accounted for 47% of the claims. It’s important to note that the majority of the claims could have been prevented with structured, and systematic communication techniques, and hand-off report tools.

TYPES OF COMMUNICATION

For purposes of this blog, I’ll be referring to verbal, and written forms of communication within the healthcare setting. Verbal communication includes, but is not limited to, hand off reports, critical events, status update reports to providers, provider to provider communication, and provider to patient communication. An examples of written communication includes documentation within the legal medical record. It’s important to consider the medical record as a legal document which serves as the most important document for defense of an alleged negligent action, or medical malpractice claim.

RISK MANAGEMENT

There are specific risk management strategies that can promote patient safety, while reducing the risk of medical malpractice allegations for nurses, providers, and hospital systems. For example, creating safe multidisciplinary learning spaces to practice effective communication techniques during critical events. This can be done in the form of implementing and requiring regular multidisciplinary simulation training.

The SBAR technique is a communication strategy that should be practiced, and utilized during hand-off reports, critical events, and status updates to providers. SBAR is a mnemonic that is designed to prompt essential communication elements.

S: Situation – state the patients current condition, reason for admission

Example – Dr. Kim, this is Sharon Jones from labor and delivery. I have Ms. Holland in room 217, a 41-year-old primiparous who has been having a persistent Category II fetal heart rate tracing for 1 hour now.

B: Background – provide relevant medical history, complications

Example – She is of advanced maternal age with an in vitro pregnancy who has a history of chronic hypertension. She was admitted for an induction of labor at 39 weeks 2 days. She received Cytotec for cervical ripening last evening, and has been on Pitocin since this morning.

A: Assessment – summarize the findings from the physical exam, monitoring results

Example – She has a persistent Category II fetal heart rate tracing that has not transitioned back to a Category I tracing with intrauterine resuscitative efforts. I’m concerned because the tracing is now showing minimal variability, absent accelerations, with recurrent late decelerations. The Pitocin has been off now for 1 hour, and interventions remain in progress.

R: Recommendation – suggest next steps for care such as interventions, further monitoring

Example – I need for you to come to the bedside now and evaluate the fetal heart rate tracing and her labor progress.

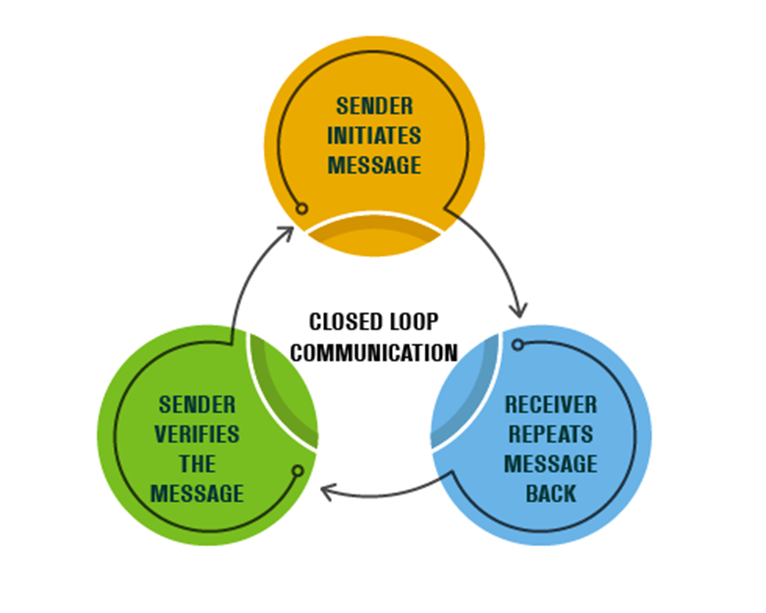

Another method to promote positive patient outcomes, while reducing the risk of litigation, is use of closed-loop communication. In closed-loop communication, the person receiving the instruction or information (receiver) repeats it back to make sure the message is understood correctly. The sender confirms to “close the loop” by verifying the message. This communication tool protects patients from communication errors that can result in adverse outcomes. Closed-loop communication is not just for critical events as it’s encouraged to be used in daily practice to ensure a shared mental model across the many specialties within the healthcare setting.

Example:

Sender: Dr. Smith –

Nurse Jones, please administer 1gram of tranexamic acid IV now to Mrs. Potts.

Receiver: Nurse Jones

Dr. Smith, I’m going to administer 1 gram of tranexamic acid IV now to Mrs. Potts.

Sender: Dr. Smith –

Nurse Jones, correct, you are administering 1 gram of tranexamic acid IV now to Mrs. Potts.

The read back and verify process reduces the risk of communication errors, failures, and delays. It’s recommended that critical findings, test results, and orders be reported verbally (by the sender), then read back by the receiver.

The performance of multidisciplinary board rounds, and bedside report have been shown to promote assessments by all specialties. There’s greater communication among healthcare teams, patients and their families while promoting collaborative decision making. There’s greater continuity of care through coordinated efforts, and greater patient and family engagement in the care delivery process. Both methods reduce the risk of errors by ensuring all perspectives are considered.

Hand-off communication is considered a high-risk activity as distractions and interruptions can serve as barriers to effective nurse and provider hand-off report. This can lead to preventable and costly medical errors, as well as increase the risk of litigation. It’s recommended that a quiet environment be used for hand-off report to promote focus. Hand-off report should be completed separately from other nursing actions, and should include the patient and family to decrease medical errors and enhance communication between the healthcare team and the patient. Active participation by patients and family members promotes patient safety by allowing patients and families to clarify and correct potential inaccuracies. Additionally, it’s recommended that a structured format be utilized to keep discussions concise and on topic. Hand-off tools are recommended as they promote continuity of patient care, while reducing miscommunications.

Efforts should be made to reduce the risk of duplicative documentation as this can be a source of risk to hospital systems, provider, nurses and patients. Duplicative documentation can lead to wasted provider and nurse time, damage to the integrity of the medical records, and medical errors. Standardized documentation checklists can reduce this risk. Additionally, regular chart audits can be done to observe documentation practices, to identify and reduce redundancies and / or omissions.

Communication with providers must be documented in the medical record. Ensure that entries include the name of the provider you spoke with, as well as any changes in the plan of care, and new orders received.

CLOSING THOUGHTS

Documentation is the most time consuming medical and nursing activity which is prone to omissions. There are significant consequences for documentation inaccuracies and omissions such as communication errors, denied insurance reimbursement, lost information for data capture, patient harm, and increased difficulty to defend in litigation.

When documenting in the medical record, remember that the medical record is a legal document. This legal document serves as the most important source of defending allegations of negligence. Healthcare providers and nurses must document objectively, timely, accurately, completely, appropriately, and legibly.

REFERENCES

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Complying with Medical Record Documentation Requirements https://www.cms.gov/outreach-andeducation/

- Documentation for Nurses: Back-To Basics, 2024. NSO Documentation

- Humphrey et al., 2022. Frequency and nature of communication and handoff failures in medical malpractice claims. Journal of patient Safety.

- Medicare-learning-networkmln/mlnproducts/downloads/certmedrecdocfactsheet-icn909160.pdf © 2024 Edie Brous

- NSO, Nurse Professional Liability Exposure Claim Report, 4th edition. www.nso.com/nurseclaimreport

COMMENT & SHARE: How has documentation influenced a medical legal outcome for you?