Fetal heart rate (FHR) pattern interpretation, communication, and documentation is a common area of liability. Reviewing the standards of care that support verdicts, as well as learning from past plaintiff, and defense counsel allegations, aids in the ability to bridge the gap between perinatal medicine, and the law.

In this blog, I’ll be reviewing a medical malpractice birth injury case with a theme specific to failure to monitor, as well as failure to identify, and act on a non-reassuring fetal heart rate tracing. I’ll discuss allegations from both the plaintiff and defense counsels that led to the plaintiff verdict. Facts of the case will be reviewed, and medical legal risk reduction strategies will be offered, specific to fetal heart rate monitoring interpretation, communication, documentation, and education. The referenced risk reduction strategies represent current evidence-based standards of care specific to electronic fetal monitoring.

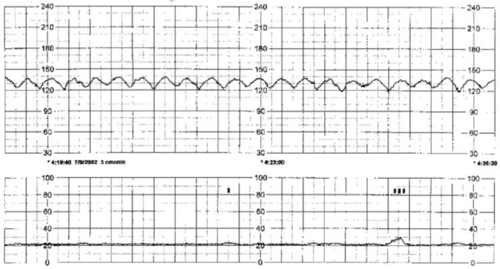

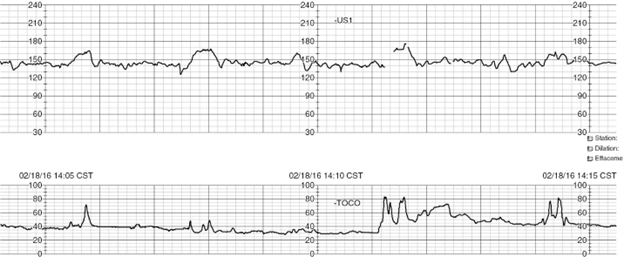

Case Facts: On April 4, 2013, Ms. Jones, a 24-year-old, who was 40 weeks pregnant, presented to University Medical Center for a routine prenatal exam, and reported she was experiencing some contractions. She underwent a non-stress test, which was completely normal, and reassuring. Jones was sent home, and was instructed to return for routine testing one week later. That night, April 4, 2013, at approximately 2:01 a.m., Jones was admitted to the University Medical Center’s triage unit for observation after she reported decreased fetal movement. Jones was evaluated in triage with a series of tests, including a non-stress test, and an attempted vibroacoustic stimulation. The non-stress test was not reactive, and the vibroacoustic stimulation failed. The resident doctors admitted Jones for non-reassuring fetal well-being, and delivery for fetal distress at approximately 4:20 a.m. At approximately 5:20 a.m., Jones was transferred into a labor room from triage at the hospital’s labor and delivery unit. Instead of performing a cesarean section for non-reassuring fetal well-being, and fetal distress, at approximately 7:53 a.m., Jones was induced for a trial of labor with the induction agent Cervidil (Dinoprostone). The fetal heart rate remained non-reassuring throughout Jones’ labor according to all medical records, and all testimony at trial. After approximately 11 hours of non-reassuring fetal heart rate tracing, and a failed induction of labor, Jones was evaluated by a board-certified attending physician for the first time at 1:05 p.m. Following the attending physician’s evaluation, a decision was made to proceed with an emergency cesarean section for fetal distress, according to numerous medical records. At approximately 1:49 p.m., Jones gave birth to plaintiff newborn Jones. The birth was performed by cesarean section. Newborn Jones was admitted to the hospital’s neonatal intensive care unit, and remained an inpatient for three weeks.

Plaintiff Counsel Allegations: Plaintiffs’ counsel alleged that the party sued was negligent in its treatment of Jones and that it failed to deliver her unborn baby immediately by cesarean section, and instead induced her with a contraindicated induction of labor medication. Counsel asserted that it was a violation of the standard of care to induce Jones for vaginal delivery, despite obvious, and documented non-reassuring fetal well-being, and fetal distress for a period of about 12 hours. The experts opined the nursing staff failed to properly assess, and analyze the fetal heart monitor, and the signs of fetal distress, failed to properly communicate with the attending physicians, failed to advocate for the safety of newborn Jones, including preventing the administration of a contraindicated medication, and advocating for earlier necessary delivery. The Jones’ maternal fetal medicine expert, and obstetrical expert testified that the attending physicians at the sued hospital deviated from the standard of care by failing to personally evaluate Jones considering the documented findings of non-reassuring fetal well-being, and fetal distress. The experts stated the attending physicians failed to properly oversee the resident doctors who were managing Jones improper induction. Ultimately, the experts opined that all of the attending physicians, and the residents deviated from accepted practice by attempting to induce Jones instead of performing an immediate cesarean section at or around the time she arrived to the hospital with identified fetal distress. The maternal fetal, and obstetrical experts concluded that had newborn Jones been delivered by cesarean section, as was required by the standard of care, he would not have suffered from brain damage

Defense Counsel Allegations: Defense counsel contended nothing it did was negligent, and that Jones’ brain damage was caused by an undiagnosed, in utero infection that occurred sometime before April 4, 2013. The defense contended there was no significant hypoxia since the cord gases showed normal oxygen, and only mild acidemia that would not account for the significant brain damage. There were other objective laboratory results that could only be explained by an event more than 24 hours prior to delivery. The only explanation that would explain everything was an in-utero infection, supported by chorioamnionitis on the placental pathology, and the mother’s complaint of decreased fetal movement for 24 hours. Furthermore, the monitor strips, and other information required continued monitoring but not an immediate or emergency cesarean section. The hospital’s expert neonatologist testified that there was an in-utero event that caused brain damage at least 24 hours prior to delivery. The most likely cause of the brain damage, based on laboratory results including the cord gases, was an infection that occurred at least 24 hours prior to the delivery, and an earlier delivery would not have changed the outcome. The defense’s expert in obstetrical nursing opined that the fetal monitor strips were stable throughout, that the nursing monitoring was within the standard of care, and that there was no reason for the nurses to “go up the chain of command” to suggest an immediate cesarean section. The hospital’s expert in maternal fetal medicine testified that the cord gases ruled out hypoxic injury during the time of the hospitalization. Additional objective laboratory evidence clearly supported an injury at least 24 hours prior to delivery. This was supported by Jones’ complaint of decreased fetal movement on arrival at the hospital, and chorioamnionitis on the placenta pathology report. Furthermore, the fetal monitor strips were stable throughout Jones’ course at the hospital, and there was nothing requiring a decision to proceed to immediate cesarean section in this first-time mom until that decision was reached.

Result: Plaintiff verdict in the amount of $53 million. Injury type(s): brain-cerebral palsy; mental/psychological-birth defect; mental/psychological-learning disability; mental/psychological-cognition, impairment; pulmonary/respiratory-hypoxia

Standard of Care Takeaways:

- Fetal heart rate (FHR) pattern interpretation, communication, and documentation is a common area of liability, and patient harm.

- Use of the standardized nomenclature recommended by the National Institute of Child Health, and Human Development (NICHD) to describe FHR patterns in all professional communication, and medical record documentation is the standard of care.

- FHR assessment must include baseline FHR, variability, presence or absence of accelerations, and decelerations, and pattern evolution when communicating normal, abnormal, and indeterminate FHR patterns.

- Ensure that agreed upon definitions of fetal well-being are established, and documented on admission prior to induction or augmentation of labor, initiation of epidural analgesia, patient transfer, and discharge.

- Develop common expectations for intrauterine resuscitation based on the presumed etiology of the FHR pattern.

- Establish agreement among team members specific to which types of FHR patterns require bedside evaluation by the primary (supervising or collaborating) care provider, and timeframe involved.

- Organizations should require ongoing multidisciplinary fetal monitoring education. Organizations should require all nurses, physicians, residents, and advanced practice RN’s (midwives, nurse practitioners, physician assistants) responsible for care of pregnant women to demonstrate competency in interpreting electronic fetal monitoring (EFM) data.

Closing: Birth injury cases allegedly involving an acute ischemic event during the labor course can be challenging in the absence of understanding the physiology behind fetal monitoring interpretation. Additionally, knowledge of expected communication, and documentation specific to clinical findings are crucial to understand in an effort to defend a birth injury case with a theme central to failure to monitor, and/or failure to identify, and act on a non-reassuring fetal heart tracing.

Resources:

AAP, ACOG (2017). Guidelines for Perinatal Care. 8th edition.

AWHONN (2021). Perinatal Nursing, 5th edition.

Miller et al., (2022). Pocket Guide to Fetal Monitoring, A Multidisciplinary Approach. 9th edition.

P.S. COMMENT AND SHARE: What do you find to be the most challenging aspect of reviewing birth injury cases with a case theme related to fetal monitoring?

Barber Medical legal Nurse Consulting, LLC is available to support your efforts in making sense of the maternal labor records, while educating your team on fetal heart rate strip interpretation.

Email: Contact@barbermedicallegalnurse.com.